Governments frequently use transitional justice mechanisms to restore peace and justice following widespread human rights violations. These mechanisms encompass a range of strategies, including granting amnesties, the pursuit of accountability, and undertaking truth-seeking missions.[i] Granting someone amnesty is a legal measure that involves the official disregard of one or more criminal offences, effectively waiving any punishment that would normally result from those acts. The goal of amnesties is to end conflict and promote reconciliation, assisting in the restoration of normalcy within a country dealing with the aftermath of a crisis.[ii]

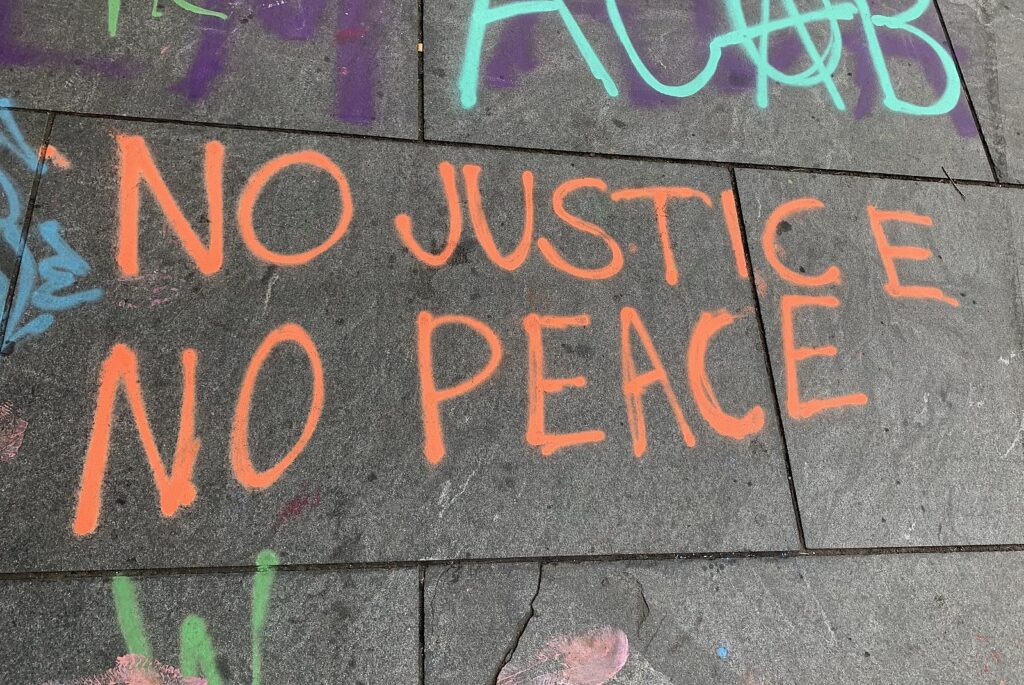

Positioned at the intersection of law, morality, and human rights, amnesties incite a contentious debate. While some people do believe in their power to encourage reconciliation many critics argue that granting amnesty undermines the pursuit of justice and allows perpetrators to avoid accountability for the atrocities they committed. At the heart of the debate is the complicated balance between peace and justice. Specifically, whether these goals are complementary or in opposition, and what justice means in the context of peacebuilding. Do peace and justice exist in harmony, or must one be sacrificed for the other? Does granting amnesty actually promote peace, and if so, for whom?

Amnesties: failures and shortcomings

Between 1991 and 2002, Algeria’s civil war saw several attempts at amnesty to end the conflict between the military regime and Islamist militants. In 1995 and 1999, the government offered amnesty in an effort to encourage surrender. However, these efforts failed to achieve long-term peace due to several factors. Firstly, the initiative required perpetrators to ‘submit’ to authorities, which implied admission of guilt. This requirement acted as a significant barrier, as perpretators refused to admit guilt even if they were not prosecuted. Importantly, there was also lack of transparency regarding the number of individuals granted amnesty, as well as limited prosecution of perpetrators. The ambiguity surrounding the application of amnesty undermined trust in the process. Overall, these shortcomings resulted in the failure to comprehensively address the grievances and political roots of the conflict, thus leading to ongoing violence.

Algeria repeated its attempt to grant amnesty under the Charter for Peace and National Reconciliation in 2005, extending it even after resistance had decreased. The charter’s approval was opposed, particularly by victims and human rights activists, because it lacked conditions for truth and justice. The country’s amnesty policy put stability and the end of direct violence ahead of justice and active peace-building efforts. While it was successful in reducing the number of militants, it did not address the underlying causes of the conflict or provide relief to victims.[i] The question remains whether Algeria truly achieved peace by sacrificing justice or simply a temporary cessation of conflict. Indeed, the answer depends on one’s definition of peace. Amnesties may have resulted in negative peace by preventing direct violence, but their overall positive impact on the community is unclear. When considering positive peace, characterized by the absence of structural injustices and violence, it becomes evident that this goal was not truly achieved.

Notable figures, including Augusto Pinochet and Slobodan Milosevic, sought amnesty to avoid prosecution. In cases like these, amnesties appear to be deeply unjust because they allow individuals responsible for grave human rights violations to avoid accountability and consequences. Amnesties, when used to shield perpetrators from accountability, send a dangerous message: human rights violations can go unpunished. This breeds resentment and undermines the prospects for genuine reconciliation and lasting peace. Peace without justice can be fragile and unsustainable.

Amnesties for good

In Colombia, a law enacted in 2016 granted amnesty to FARC members, state officials, and civilians involved in acts related to the armed conflict. Individuals charged with crimes against humanity, massacres, or rapes, on the other hand, faced a specialised judicial procedure. This process could have resulted in alternatives to imprisonment, such as participation in reparation programmes, provided the perpetrators fully disclosed the acts they were accused of committing. This approach strikes a fine balance between accountability and reconciliation. Colombia recognized the complexities of its conflict by offering conditional amnesty while holding perpetrators of the most heinous crimes accountable. This not only facilitates justice but also encourages truth-telling and participation in efforts to rebuild conflict-affected communities. In this way, amnesties can be used to promote transparency, healing, and sustainable peace.

Amnesties also serve as a possible response to the flaws in the retributive justice system. Retribution, by its nature, is not peaceful, and its use often fails to deliver true justice to victims. Passing amnesties, to an extent, recognizes these limitations and offers a flexibility that is more focused on restoration. For example, Liliany Obiando, the director of Colombia’s largest agriculture union, was imprisoned on charges of aiding a terrorist organisation after authorities discovered evidence that allegedly linked her to a FARC leader. Obando was granted amnesty in 2012. Upon reflection, how was having her, a single mother, teacher and sociologist, imprisoned really contributing to peace? The perspective that amnesties equate to impunity, and that retribution is synonymous with accountability, is misleading, and inherently wrong. Having an increased awareness of what accountability entails illuminates the potential for amnesties to play a more constructive role in post-conflict justice and peacemaking, fostering genuine reconciliation.

To amnesty or not to amnesty

Analyzing examples like Algeria and Colombia reveals the various outcomes and ethical implications of amnesty policies. While Algeria’s amnesty policy failed to address the root causes of conflict and hampered reconciliation, Colombia’s more nuanced approach offers a more promising path to peace. When considering whether to grant amnesty or not, it is clear that there is no simple answer because the issue is complex and case-specific. What is evident is that transitional justice mechanisms should include more than just top-down legal interventions. Amnesties can be implemented as part of a larger framework that prioritizes truth-seeking and community participation. The goal should be to create a future where peace and justice are not mutually exclusive but mutually reinforcing pillars of a peaceful society.

What do you think?

- What does justice mean to you?

- How can societies balance the need to pursue accountability for crimes with the desire for reconciliation and forgiveness? Are these things mutually exclusive?

- How do your personal biases influence your views on the effectiveness and morality of amnesties in addressing societal conflicts?

- Is the relationship between justice and peace as complicated as it seems?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy (Imperfect) Justice via Gacaca in Rwanda, The Place of Neutrality in Peace Work and Colombia: The long road to peace

Zoe Gudino, April 2024

References

- [i] Fraihat, I. and Hess, B. (2017). For the Sake of Peace or Justice? Truth, Accountability, and Amnesty in the Middle East. In: Transitional Justice in the Middle East and North Africa. Oxford University Press, pp.61–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190628567.001.0001.

- [ii] International Committee of the Red Cross (2017). Amnesties and international humanitarian law: Purpose and scope. International Review of the Red Cross.