Rwanda experienced one of the deadliest conflicts in the second half of the 20th century. Since the country gained independence from Belgian control in 1962, tensions had grown between different ethnic groups, in particular between the majority Hutu population and the minority Tutsi. (In fact, tensions had existed – and been stoked – long before then, as this article underlines.) In October 1990, civil war broke out; and this culminated four years later in three months of particularly brutal violence, triggered by the assassination of President Habyarimana. This violence is now known as the Rwandan genocide (April-July 1994).

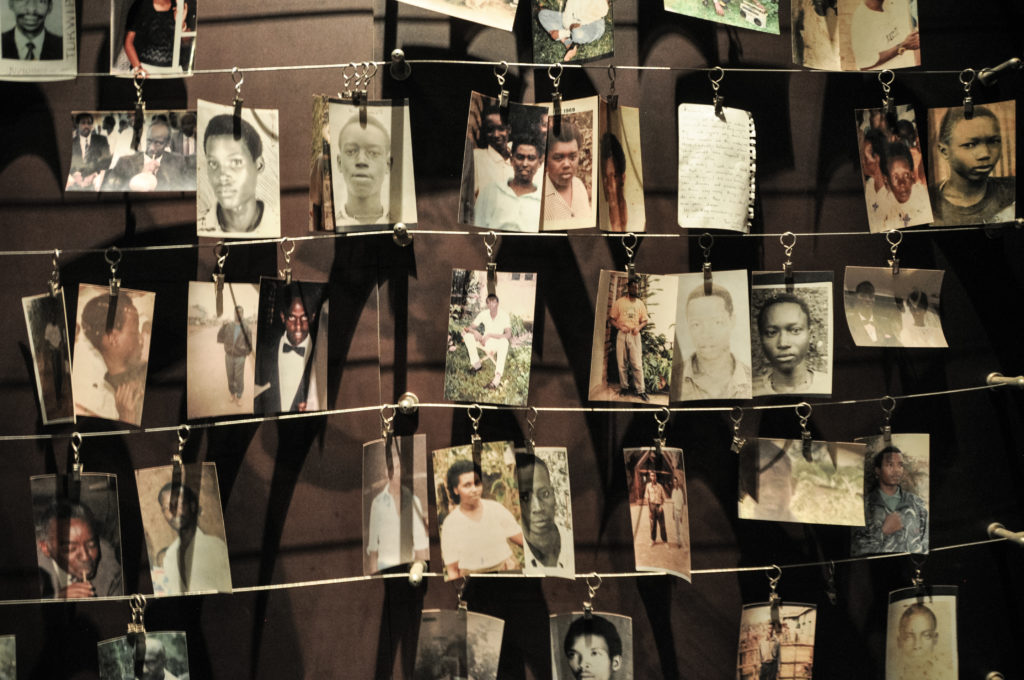

Somewhere between half a million and a million people were killed. The majority of victims were Tutsi, killed by Hutu gangs. While some of these murders were committed by soldiers, others were committed by police and informal militias, made up of ordinary people: former neighbours and friends who turned on each other. Hundreds of thousands of women were also brutally raped. The genocide ended when the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), composed mostly of Tutsi, overthrew the Hutu government and seized control of the country.[i]

Peace and Justice

The new Rwandan government recognised that post-conflict justice was a vital step in establishing peace. Since the end of the Second World War, a pattern had been established whereby perpetrators of genocide were tried in international courts, with legal proceedings focusing primarily on those in command. The United Nations established the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, which prosecuted high-level military, political and religious leaders, securing around 60 convictions. Within Rwanda, national courts also prosecuted many perpetrators; but one problem facing the justice system was the sheer number of ordinary people who had committed acts of genocide. Without justice, how could victims re-settle in their old homes, knowing that many of their near-neighbours had committed extreme violence against each other?

Prosecuting all perpetrators through traditional legal systems was impractical, given the numbers of people involved, so an alternative (parallel) solution was devised: a local, grassroots community court system known as ‘gacaca’, which had previously been used to settle relatively minor local issues.

‘Rwanda put most of the population on trial – as perpetrator, victim, bystander, rescuer and judge — to make accusations and evaluate confessions. In opting for mass justice, Rwanda chose local, community-based justice over other post-conflict reconciliation mechanisms such as amnesties or truth commissions. In consultation with its foreign donors, the government made the gacaca courts its primary legal mechanism to generate a truthful record of who did what to whom during the 1994 genocide.’

Susan Thomson, Rwanda’s Gacaca Courts: https://journals.openedition.org/temoigner/3537?lang=en

The idea was for local villages to organise their own trials, or ‘gacaca’. These focused on suspects accused of individual acts of violence, not those accused of planning the genocide (which was taken care of by the International Criminal Tribunal). Between 2005 and 2012, over 12,000 gacaca were set up across Rwanda, and around 1.2 million people were tried in them, with a conviction rate of c. 65%. Some of those found guilty were given long prison sentences; others (especially those who confessed and sought forgiveness from their victims) were required to do forms of community service, including rebuilding places damaged by the conflict.

At its best, the gacaca system made individuals visibly accountable for the roles they had played in the genocide and enabled communities as a whole to piece together a narrative of the conflict, both of which are important steps in peace-building.[ii] It was hoped that, as well as documenting crimes and bringing a sense of post-conflict justice, these local, community-based trials might also support processes of reconciliation and forgiveness. There is evidence that this did happen at times, as this BBC story illustrates: ‘I forgave my husband’s killer – our children married‘. However, as many have noted, the gacaca court system also had many flaws and has only been partially successful in securing post-genocide justice and promoting sustainable peace-building.

‘Some Rwandans have welcomed the courts’ swift work and the extensive involvement of local communities, stressing that gacaca has helped them better understand what happened in the darkest period of the country’s history and has eased tensions between the country’s two main ethnic groups (the majority Hutu and minority Tutsi). Others are more skeptical: some genocide survivors complain that not all perpetrators were arrested or punished adequately for their crimes. Some of those convicted and sentenced to decades in prison maintain that trials were seriously flawed, that private individuals and government authorities manipulated the course of justice, that gacaca became politicized over the years, and that ethnic tensions remain high. On both sides, there are doubts, as well as tentative hopes, about gacaca’s contribution to long-term reconciliation.’

‘Justice Compromised’, a Human Rights Watch report (May 31, 2011): https://www.hrw.org/report/2011/05/31/justice-compromised/legacy-rwandas-community-based-gacaca-courts

In some cases, gacaca trials exacerbated ethnic divisions rather than resolving them: every Hutu became a suspect, every Tutsi a judge. In fact, many Hutus, fearing counter violence, fled Rwanda and remain displaced to this day. Secondly, it has become clear that Rwanda’s new Tutsi-dominated government (still in power) built some of its legitimacy and authority around of the gacaca courts, with patronage and political interference sometimes getting in the way of justice.[iii] Anuradha Chakravarty discusses this in her book Investing in Authoritarian Rule: Punishment and Patronage in Rwanda’s Gacaca Courts for Genocide Crimes, reviewed by Laura Seay for the Washington Post.

For all their failings, evidence suggests that the gacaca court system was successful in bringing about some reconciliation amongst communities and in building peace at local levels. This is no mean feat in the wake of genocide. For that reason, while we should continue to examine their flaws, we can also draw some inspiration from Rwanda’s gacaca as we consider different mechanisms for post-conflict justice and peace-building in other contexts. Peace-building requires creativity and experimentation, to give dialogue, reconciliation, healing and rebuilding a chance. We can learn a great deal from this large-scale experiment, which was devised and deployed in the aftermath of some of the worst violence our world has ever seen.

What do you think?

- What can local, community-based trials achieve in the aftermath of conflict that international justice systems cannot?

- What are the risks and pitfalls of justice systems like Rwanda’s gacaca courts?

- What can this example of post-conflict justice tell us about the building blocks and challenges of peace-building?

- What positive aspects of the Rwandan gacaca system would you like to see in future post-conflict reconciliation and peace-building processes?

- Must peace-building always involve justice?

- What forms of justice are more conducive to sustainable peace-building than others?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also like ‘Intergroup Contact Theory‘, ‘Pride: peace in social justice‘, ‘Andromache’s Serach for Post-Conflict Peace‘, and ‘Journey for Forgiveness‘.

Margaux de Seze, December 2022

[i] Department of Public Information (2012) Rwanda, genocide, Hutu, Tutsi, mass execution, ethnic cleansing, massacre, human rights, Victim Remembrance, education, Africa, United Nations. United Nations. Available at: https://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/backgrounders.shtml (Accessed: October 31, 2022).

[ii] Timothy Longman (2009) An Assessment of Rwanda’s Gacaca Courts, Peace Review, 21:3, 304-312, DOI: 10.1080/10402650903099369

[iii] Seay, L. (2021) Analysis | Rwanda’s Gacaca Courts are hailed as a post-genocide success. the reality is more complicated., The Washington Post. WP Company. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/06/02/59162/ (Accessed: October 31, 2022).