‘I’ve come to realise that a peace treaty is only the beginning of a new era, a fragile document that must be filled with life, […] and that social justice and major changes are needed to put an end to the vicious circle of violence in Colombia.’

Uli Stelzer, 2019

Colombia is an interesting case study as one of the most recent examples of a successful peace process; a success which was internationally recognized through the award of the Nobel Peace Prize 2016 to the Colombian president Juan Manuel Santos for his role in promoting efforts towards peace in the country. This item in our museum is an analysis of the documentary Colombia: The long road to peace after the civil war by Uli Stelzer, made for the German state-owned broadcaster Deutsche Welle and shared with the public via Youtube in 2019. The commentary integrates quotes from the Nobel Lecture of Juan Manuel Santos, ‘Peace in Colombia: From the Impossible to the Possible’, to emphasize the message of peace that Colombian people sent through the words of their president on receiving the Nobel Peace Prize.

‘[…] peace does not belong to a president or a government, but to all the Colombian people, because we must build it together. That is why I receive this prize on behalf of nearly 50 million Colombians – my fellow countrymen and women – who finally see the end of more than a half-century nightmare that has only brought pain, misery and backwardness to our country. And I receive this prize – above all – on behalf of the victims, the more than 8 million victims and displaced people whose lives have been devastated by the armed conflict.’

Juan Manuel Santos, 2016

Colombia: The long road to peace after the civil war is available at: https://youtu.be/xO6AnTc0OE8.

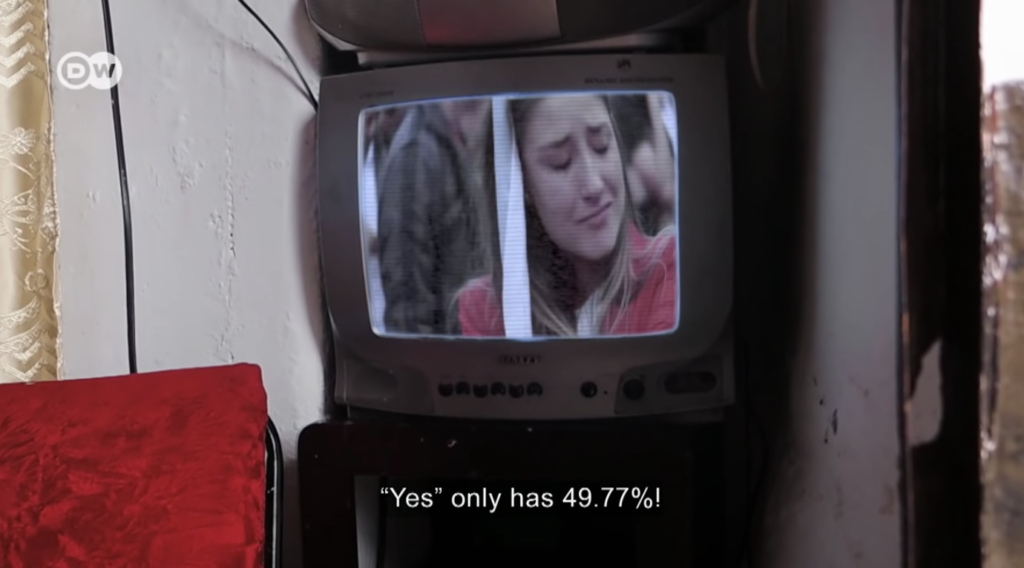

The aim of the documentary is to assess the aftermath of the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the guerrilla group FARC (the ‘Revolutionary Armed Forces of Columbia’), after about 50 years of civil war.[i] FARC’s members were mainly farmers and others involved in agriculture, and their violent actions originated in calls for more equal land access. After a popular referendum rejected the option of a peace agreement in 2016 (a result that was followed by protests), a revised peace deal was eventually signed and FARC was established as a political party. However, many challenges to peace remain, triggered by poor reintegration of ex-FARC members and failure to address the root causes of the conflict (social and economic inequality), lack of accountability for war/violent crimes and political instability.[ii]

‘But it is foolish to believe that the end of any conflict must be the elimination of the enemy. A final victory through force, when nonviolent alternatives exist, is none other than the defeat of the human spirit. Seeking victory through force alone, pursuing the utter destruction of the enemy, waging war to the last breath, means failing to recognize your opponent as a human being like yourself, someone with whom you can hold a dialogue with. […]’

Juan Manuel Santos, 2016

The first reflection that the documentary sparks relates to the results of the popular referendum on the peace agreement. Most of the population voted against it, but the documentary highlighted how those who voted ‘no’ mainly lived in cities and were not necessarily affected by the violence and social inequalities permeating the conflict. Indeed, the proposed peace agreements mainly concerned a land distribution reform, to effectively address the root causes of a conflict that started and was carried out mainly in rural areas, to establish a sustainable peace and prevent history from repeating itself.

‘That is the great paradox I have found: while many who have not suffered the conflict in their own flesh are reluctant to accept peace, the victims are the ones who are most willing to forgive, to reconcile, and to face the future with a heart free of hate.’

Juan Manuel Santos, 2016

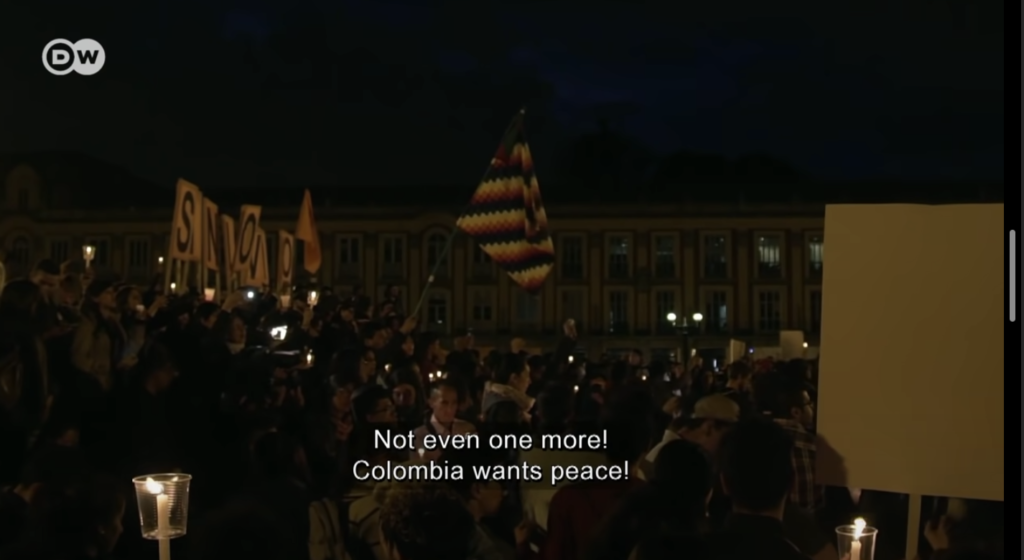

Protests in cities against the referendum results, led by students, showed the power of activism, popular uprising and education as tools to push institutions to take action towards peace. At last, the peace agreement was signed, and in January 2017 FARC members marched one last time to leave their weapons in the hands of UN representatives. This event highlights the crucial role that the UN has played in promoting and supporting peace-building processes since its establishment after WWII, opening a discussion on the role of and relationship between state power and international institutions in conflict resolution.

However, the election of the right-wing politician Duque in 2018 underlined the detrimental impact that national political shifts can have during the post-conflict phase. A loophole was introduced in the process of land redistribution, allowing access to big international corporations. The commercialization of agriculture revived the struggle that rural and indigenous peoples had long been experiencing, pushing many former FARC members to take up weapons again.

This relates to the lack of reintegration programs for ex-fighters, which are an essential element of sustainable peace-building that addresses the causes of conflicts but also builds facilities and conditions for future peace. In this regard, the investigations into war crimes perpetuated by both guerrilla groups and paramilitaries – including sequestrations, rape, displacement – were crucial. The creation of a special jurisdiction for a Truth Commission gave hope for change as well as compensation to the victims, allowing them to heal and be in the position to contribute to building a future long-lasting peace in Colombia.[iii]

‘I am told by scholars that the Colombian peace process is the first in the world that has placed the victims and their rights at the center of the solution. This negotiation has been conducted with a heavy emphasis on human rights. And that is something that makes us feel truly proud. Victims want justice, but most of all they want to know the truth, and they – in a spirit of generosity – desire that no new victims should suffer as they did. […] We also achieved a very important objective: agreement on a model of transitional justice that enables us to secure a maximum of justice without sacrificing peace.’

Juan Manuel Santos, 2016

In his Nobel Lecture, president Santos summarized the key steps of the peace process and discussed the connection between peace-building, restorative justice, inclusive decision making and governance, and conservation of Colombia’s rich biodiversity by progressively reducing cocaine crops. In fact, the Colombian peace process offers important reflections on the interrelation and co-dependence between sustainable peace, justice, social equality and environmentalism. It helps to stretch how we think about peace-making and peace-keeping and peace itself, presenting social and environmental justice as intrinsic to sustainable peace-making.

What do you think?

- In regards to the referendum on the peace agreement, to what extent should peace be a choice that civilians can vote on?

- What balance of influence and involvement do you think international organisations like the UN, governments, ordinary citizens and victims of conflict should have in peace-building processes?

- How important are investigations into war crimes for successful peace-building and peace-keeping processes?

- How important are reintegration programmes for former fighters in peace-building and peace-keeping processes?

- When it comes to advocating for social or economic justice, to what extent are violence and conflict more effective than peaceful protests and popular uprising?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy ‘Pride: peace in social justice and the power of solidarity‘, ‘Fractured Peace‘, ‘Two Neighbours‘ and items with the tag ‘Activism‘.

Lia Da Giau (May 2022)

[i] Some interesting overviews and analysis of the Colombian Civil War and its causes can be found here: https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2017/07/civil-war-colombia; http://www.midlandshistoricalreview.com/the-underlying-dynamics-of-colombias-civil-war/; and https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0738894218787780.

[ii] Here are some of the challenges of post-conflict Colombia explained: https://uniandes.edu.co/en/news/science-technology-and-health/regional-development/postconflict-rural-colombia; https://nacla.org/news/2019/12/12/rejecting-inequality-and-state-violence-colombia; and https://nacla.org/news/2018/08/10/colombia-will-peace-continue-costing-lives.

[iii] You can hear about the Colombian ‘Truth Commission’ in this podcast. To read more about restorative justice in post-conflict Colombia: https://doi.org/10.1093/jicj/mqaa022; https://www.ictj.org/location/colombia; and https://www.jep.gov.co/Sala-de-Prensa/Documents1/What%20is%20the%20Special%20Jurisdiction%20for%20Peace.pdf.