Inspired by our discussions of different methods of visualising peace – and in particular, by lots of different ‘Conflict Textiles‘ – I decided to experiment with making my own collage. This piece was created to represent the conflict and subsequent peace process in Northern Ireland. I drew inspiration from various textiles, murals, and academic research conducted in the region.

As the closest neighbour of Great Britain, Ireland has been in a state of near-perpetual conflict since the Norman invasions in the 12th century (Cairns, 1987). In 1920 the Island of Ireland was changed forever when the United Kingdom partitioned it into 32 counties and two nations: The Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland (Government of Ireland Act, 1920). This was a partial victory for the people of the Republic, whose population consisted mainly of Catholics who had suffered under British rule. In the north of the island, the new state consisted of a majority Protestant population who were largely in support of being part of the United Kingdom (Ferguson and McKeown, 2016). However, like many that separate communities and ethnic groups, the border was not perfect and left a significant minority of Irish Catholics in a country isolated from their community.

This sparked conflict, as Catholic communities in Northern Ireland fought to be reunited with the Republic, culminating in the 1960s when “The Troubles” began. With differences of affiliation largely aligned to religious identity (Moxon-Browne, 1991), ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland spanned 30 years, from 1968 to 1998, leading to the deaths of over 3600 people and the injury of 40–50,000 more (Ferguson and McKeown, 2021). In 1998 a peace agreement was created between the British government and paramilitaries from both sides in the region, creating a new Northern Irish general assembly where executive power would be shared between representatives from the Catholic and Protestant communities (UK Government, 1998). The region has continued to see unrest since the “Good Friday Agreement”. This unrest has become particularly prominent since the announcement of a sea border between Northern Ireland and the United Kingdom, in connection with Britain’s exist from the European Union (Brexit) (Hirst, 2021). The Northern Irish Protocol, which is part of the Brexit deal, threatens the fragile peace present in Northern Ireland. This piece represents my research into the area and the current state of peace there. The analysis below explains the various aspects of the collage. I hope you enjoy it.

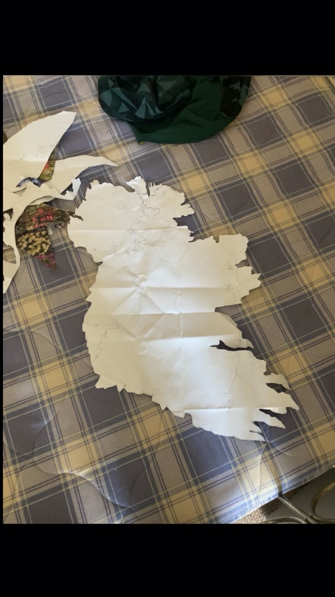

The material that I used to cut out the shape of Ireland is from the area in Australia where I was born, Lake Grace. I felt this name was fitting as this conflict is often articulated and perceived as a clash between two branches of Christianity: Protestants and Catholics. The choice of the Lake Grace poster is connected to the concept of Divine Grace. Divine Grace, by definition, refers to an influence that pushes people towards virtuous impulses, something distinctly lacking during this conflict – hence the name ‘Fractured Grace’. Leaving the term ‘Grace’ exposed in the piece indicates there is still a possibility for peace and virtue in Northern Ireland.

The flowers on the material are native to Lake Grace, Australia, and were photographed by my godmother. I included this in the piece to bring some of my heritage and story into the work. Lake Grace represents purity and renewal, and its flowers are an extension of that. Nature and flowers are commonly associated with peace and feature heavily in modern and ancient depictions of peace. For example, the Ara Pacis Augustae, an altar of peace from the Roman empire, features extensive floral designs (Becker 2020).

Flowers can represent many different things, such as death, renewal, and prosperity, to name just a few. I selected this material for the variety of colours present in the flowers which could symbolise different things. For example, the colour purple is linked to themes of mourning in Catholicism. The colour is worn during funerals in Catholic churches and is used throughout the ceremony. Within the Catholic faith, purple represents repentance and forgiveness of sins and a sign of hope (BBC 2022). The purple flowers represent the mourning of people on all sides in Northern Ireland who have suffered violence and oppression; it also depicts hope that things will improve in the region.

The red flowers represent the bloodshed and death brought on by the conflict. Red flowers such as the poppy are often linked to war and conflict in the UK. As a bold colour, red also has associations with warnings and danger. Hence, they are used in danger and stop signs. The red flowers represent those lost in conflict and warn of dangers that lurk in Northern Ireland’s future.

The white flowers, meanwhile, represent the hope and purity of innocent bystanders dragged into the conflict – white often being linked to purity and innocence. The green flowers and foliage have obvious connotations with Ireland (in particular, the shamrock), but they also represent grassroots peacebuilding. Grassroots peacebuilding is a method of peacebuilding which utilises local knowledge and groups to build sustainable peace agreements and models (Hamidi 2018). This has been seen in several conflicts, including in Northern Ireland, where (for instance) groups of women from both sides of the conflict came together to form the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition: a group focused on writing the local woman into the Northern Irish peace process. This group played a critical role in creating the Belfast Agreement, more commonly known as the ‘Good Friday Agreement’ (Molinari 2007). The green in the collage represents the importance of these groups in achieving truly sustainable peace.

The blue in the piece symbolises several things. Initially, I thought of blue as a colour representing despair and sadness, thinking of songs like New Order’s ‘Blue Monday’. In this song, the narrator discusses the mistreatment he has received from someone he trusted (Shelton 2019). In post-conflict reconciliation efforts, trust is a fundamental emotion. Those who trust members of the outgroup are more likely to engage in reconciliation efforts (Tropp 2008). Therefore, the blue in this collage represents the break of trust between communities, leading to this conflict. However, blue can also represent new beginnings and hope; it is the colour of new horizons and oceans. This indicates that there is hope for the future of Northern Ireland if the communities in Northern Ireland can break the cycle of violence and prejudice.

Finally, the collage also contains yellow flowers. In literature, yellow has connotations of cowardice. For example, in J.D. Salinger’s “The Catcher in the Rye”, Holden describes himself as ‘yellow’, meaning cowardly (Salinger 1991). This connotation of cowardice with the colour yellow also comes across in expressions such as ‘yellow-bellied coward’, still prominent in some communities today. However, yellow is also synonymous with sunshine, positivity and light. Due to this, I want the yellow in the piece to represent hope and solidarity for peace efforts.

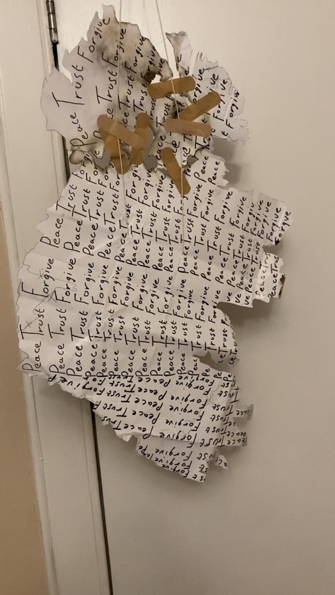

The rumpled nature of the piece speaks to broader notions of social unrest. The general ruggedness of the entire piece across all of Ireland indicates how the conflict has affected the whole island. Near the bottom, there is less distortion as the war has affected the regions less. However, the piece becomes further damaged as you get closer to the border, with burned rips in some areas. This is most noticeable near Derry and Belfast, as these regions have been affected particularly badly by the conflict.

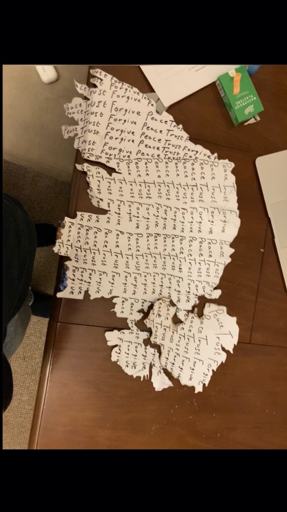

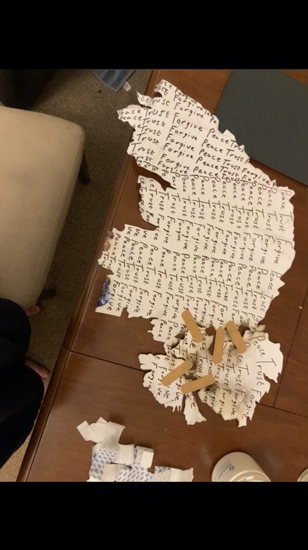

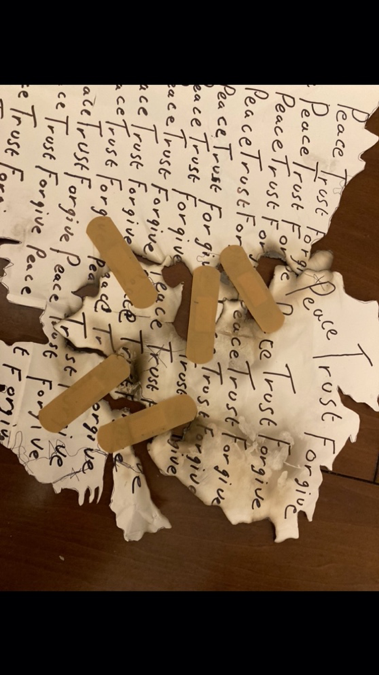

On the back I have written three words: ‘Peace, Trust and Forgive’. This reflects the narratives I have collected about the Northern Irish conflict. These three narratives can be seen in George V’s speech during the opening of Stormont (BBC 2021),The Belfast Agreement (UK Government 1998), and in the words of Senator George Mitchell who chaired the Northern Ireland peace talks which led to the Belfast Agreement (Mitchell 1999). Leaders of various groups involved in the peace process have repeatedly asked people to do the same thing to move forward, to forgive and trust outgroups to create peace in the region. These words are also related to wider research on intergroup contact theory, which states the importance of emotions such as trust and empathy to achieve peace and forgiveness (Pettigrew et al. 2011) (Tropp 2008) (Hewstone et al. 2006). Across much of my collage, these words can be seen clearly, indicating a general acceptance of this rhetoric – at least, in most of the Republic of Ireland. However, in Northern Ireland, these words have been charred, ripped and blackened, showing that the healing has been fragile at best and there is much work still to do to embed these ideas fully.

The border between Northern Ireland and Ireland has been burned, indicating the damage the conflict has done to the country. The Northern Irish conflict has left scars within the communities of Northern Ireland, which are still very much present today . This can be seen in communities divided by ‘peace’ walls. Today there are more peace walls separating communities in Northern Ireland than ever before; some sources claim over a hundred walls are still standing (Irish Times, 2022). The walls were erected in the 70s during the height of the conflict, to separate Catholic and Protestant communities. There is some irony in their being called ‘peace walls’ or ‘peace lines’, since the reality is that they mark ongoing lines of division and their role is to ‘keep the peace’ rather than to embody an existing peace. There are more of these barriers present today than ever before (Financial Times 2022). Some see this continued segregation of communities in Northern Ireland as a failure to create real peace in the region.

The Belfast Agreement was created to end the conflict in Northern Ireland and prevent continual animosity between the communities in the region. One of the main points of this treaty was to create a government which has cross-community power-sharing at the executive level, including the joint office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister and a multi-party executive. The First and Deputy First Ministers, one unionist and one nationalist, have equal powers (UK government 1998). This model ensures that both communities are represented in government. However, it means that sectarian divisions are constantly highlighted, which has led to a dysfunctional government in Northern Ireland. For example, there have been two periods since the Belfast agreement where the Northern Irish Assembly has been suspended – from 2002 to 2007 and 2017 to 2020 – leaving the country without a government for eight years out of the twenty-two since the Belfast Agreement was created (Northern Ireland Assembly 2015) (McDonald 2020). Other peace agreements which force ethnic representation in government have similarly floundered, due to the ongoing visibility of differences between groups and their supporters. This can be seen in Bosnia, for example, where there are still issues of intergroup conflict in the region since the Dayton Accords (Murer 2010). The rips at the border and plasters on my collage show how the divisions between communities in Northern Ireland are still deep, and that the use of things such as peace walls is not sustainable. Hence the two countries have been held together with old plasters which attempt to patch up divisions which need greater attention and care.

In addition, I have constructed the collage so that Northern Ireland and The Republic of Ireland appear to be pulling away from each other. This is due to the effects of the Northern Irish Protocol, the treaty created as part of Brexit. The protocol has created a sea border between the United Kingdom and Northern Ireland to prevent a hard border between The Republic and Northern Ireland. However, this new border has led to demonstrations and acts of violence from loyalist groups in Northern Ireland (Hirst 2021). Further, the former leader of the DUP resigned in protest of the Northern Irish Protocol, and the current leader has hinted they will not form a government until the treaty is changed (Edgar and Flanagan 2022; Campbell, 2022). The Northern Ireland issue maybe re-emerge with Unionist protests against Brexit from the public and politicians. Hence Northern Ireland in the collage is drifting away from peaceful relations with the Republic. The plasters placed to patch issues relating to The Troubles and Brexit are being stretched to breaking point. This represents the rising tensions in the region.

Many of the symbols used in the collage were inspired by various murals found in Northern Ireland (McGovern 2020 ; Hanman 2008). These murals are present in both communities; they are prominent across peace walls and display community heroes and para-military groups. I have used images from various murals to cover the collage as a homage to these artworks, hence the image of the balaclava and the British and Northern Irish flags. Both emblems from the Celtic and Rangers football clubs are also present. These clubs form the Old Firm derby, one of the most famous in the world. The derby is embedded in Scottish culture and highlights the divide still present due to sectarianism in the Celtic nations (McNab 2017). The emblems of the clubs have been added to this collage to represent their respective people, Celtic-Catholics and Rangers-Protestants.

I have included the emblem of the Irish rugby union team, on the other hand, since in this sport players from the Republic and Northern Ireland are brought together in one team. This is a nod to the potential reunification of the north and south to form one nation – or at least to more cordial relations and collaboration between the two. Similarly, I have included an image of St Patrick, the patron saint of both Ireland and Northern Ireland, illustrating what the two states share. I included this after hearing Sir Jeffery Donaldson discuss the saint in his debate with Sinn Féin at Cambridge (Cambridge Union 2022). I also included an image of a lapwing, Ireland’s national bird. These birds are present in the north and south and again highlight commonalities between the two nations. It also continues the nature narrative present in this piece.

The inclusion of South African images is designed to evoke reflections on the so-called ‘Apartheid state’ in Northern Ireland, a concept discussed by Republicans in the same Cambridge debate where Sir Jeffrey Donaldson spoke (Cambridge Union 2022). The South African flag can also be seen in some Catholic Murals as members of the Catholic community feel an affiliation with the struggle against the Apartheid regime (McGovern 2020). The cover of ‘The Book of Joy’ is also present as the book discusses the challenges of peacebuilding and moving on post-conflict (Tutu & Dalai Lama 2016).

What do you think?

- How would YOU visualise peace? What comes to mind when you think about depicting peace? Is it a lack of conflict, an abundance of nature, friendship and collaboration, or something else?

- How would you represent peace-making in Northern Ireland specifically? In what ways does my collage resonate with how you understand current tensions and peace-building efforts there? And what else would you include, or what would you do differently?

- How can art better inform our understanding of peace and conflict?

- Would you define this collage as a ‘visualisation or peace’ or as a ‘conflict textile’?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy ‘Peace from Pieces‘, ‘Peace Banner‘, ‘A Blank Newspaper‘, ‘Cyber Peace and Artivism‘, ‘Visualising Peace after Forced Displacement‘ and items with the tag ‘Fragile Peace‘.

You might also find it interesting to read about The Linen Memorial, an alternative, material representation of the costs of ‘The Troubles’ in Northern Ireland, and also a call to everyone to come together in contemplation of their shared grief and their shared future.

Harris Siderfin, April 2022