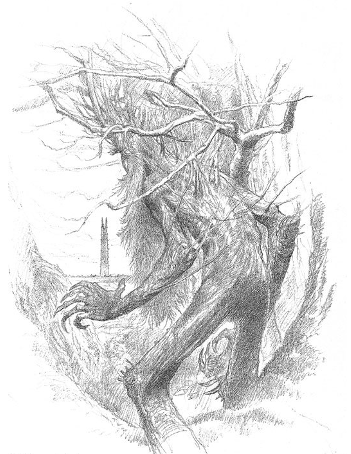

Treebeard stands in silence, like a lonely, gnarled tree in the midst of a field of tree stumps. To him, they are corpses, a bloody massacre that just shook the Entish peoples to their core. To Saruman, they are just trees; fuel for his factories, pumping black fumes in the background of the Fangorn forest. In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien creates the Ents, tree-like creatures that are also shepherds of the forest. It is, perhaps, the most glaring example of a personification of environmentalism in the story, a deeply personal wish for Tolkien to give a voice to the English countryside that he saw being invaded by technology[1]. The metaphor, even if not intended, is unmistakable: the oppressed trees, their concerns long trampled by the owner of the land, rise up against the oppressor and wage war against him. In doing so, the Ents exemplify one of the most impactful ways in which storytelling and myth can generate awareness toward environmental conflict and conservation: through the personification of the natural.

War is conflict, a struggle between two entities with agency and different desires. Kant believed that war was intrinsic to the natural state of man, an injustice inherent to our existence that must be overcome. This theory of liberalism has been adopted by modern schools of international relations.[2] He believed war to be present in our society, our lives and even our internal struggles. In contrast, peace has been believed to be a less instinctive presence. Hobbes, despite holding a vision of peace as only the negation of war, postulated that peace could be understood as a social contract come of the successful overcoming of the natural tendency for conflict, after a negotiation that satisfies all parts.[3]

It is important to point out that this concept of peace is not the only one in history, and can potentially be harmful to peacebuilding efforts due to the internalization of peace as an artificial state of being. Ancient Greek mythology, for instance, imagined a natural state of peace, a Golden Age, disturbed by progress, which brought war. [4] However, modern Western thought has traditionally associated it with being an arrangement between parties that are all conscious and sapient. This limitation has long been a barrier for more environmental visualisations of peace and peacebuilding. Throughout history, our relationship with nature has largely not been considered as conflictive or reconciliatory because nature was never regarded as an agent.

The twentieth century saw a growing sentiment toward observing nature compassionately and reconsidering its state as an agent.[5] Nature is silent, and its scale is too large to be comprehensible to human beings. That is not to say that there are no advocates that stand up for it and cry out in pain. Indigenous communities have been especially vocal throughout history about the dangers of environmental conflict, but that vision has been largely suppressed by Western colonialism in favour of economic growth. The issue that makes nature different from another afflicted group, however, is that humans have to listen closely and investigate for decades before they can determine the way in which nature is being hurt, how it’s slowly agonizing. It has no voice, but, if we want to find peace with nature to ensure our survival, we must give it a voice. One of the ways of doing so is with environmental advocates: Greenpeace, advocates like Jean-Jacques Cousteau, Jane Goodall, politicians such as Al Gore… However, almost unequivocally, these advocates are first met with rejection, scepticism and mistrust. This stems from basic psychology: no one likes to be talked down to. It is instinctual to immediately want to question anything you are being told to think, and it should be so. In order to make people sympathize with a struggle, humans have to relate to it, to empathize with the plight of the affected, and that is where mythology, fantasy and story-telling becomes valuable.

J.R.R. Tolkien was aware of this phenomenon. An Anglo Saxon scholar who also studied Classics, he had extensive knowledge of the personification of nature in myths in various traditions. To cultivate the inspirations that would, in time, grow into many of his myths, he turned to the Nordic Eddas, Finnish mythologies and Old English texts. Here is where he found his word for ent, from the Old English ’enta’, meaning giant.[6] Tolkien’s legendarium boasts an array of fantastical creatures, but, to see the examples that are most similar to the Ancient Greek and Roman deities, we have to go back to the Silmarillion, his anthology of the creation and First Age of the world of Middle Earth.

In a section named the Valaquenta, [7] Tolkien introduces us to the angelic creatures that created the world. None of them are gods; Tolkien’s Catholicism led him to create an omnipotent, benevolent god that was responsible for all of creation, Eru Ilúvatar. However, he delegates the task of building the world to these different spirits, named the Vala, who we can equate, at least in power, to the gods of Greek mythology.

One of these beings is the Valar Yavanna, who created forests and represents fertility and vegetation. Yavanna embodies the wild side of nature, not a domestic form of it like Demeter would in Greek mythology– ‘[her realm was] from the trees like towers in forests long ago to the moss upon stones or the small and secret things in the mould’. Even so, she has a gentle nature, which is telling of Tolkien’s vision of the natural world. Yavanna creates the ents as custodians of the forest in response to Aule, god of forgery, creating the dwarves. There is an antagonistic nature between industry and nature, with the dwarves represent mining, fortification-building, metal-working… all human activities that disturb the natural world. Tolkien imbues the ents with all the qualities that he saw in the natural world that surrounded them. They are old, much older than the new technologies springing up around them, which immediately elicits a sense of outrage for the unfairness of their displacement from a land they called home before anyone else. They are dwindling, losing the power they once held, and many of them are becoming silent and losing the ability to speak. The ents deeply resonated with the readers of the Lord of the Rings, and their struggle became a symbol for the fight against deforestation and the safekeeping of forest biomes.

These new mythical creatures that are entering society are vastly different from the arrogant, despotic deities that once represented nature. They are powerless, displaced, in danger of extinction. They mirror the victims of the environmental crisis of the contemporary age. They are relatable because they are personified into beings with agency, that we can equate to minorities that we have seen these atrocities inflicted upon. Treebeard initially seems not to propose any solutions to mend this relationship. Instead, in The Two Towers, he recites a poem that lists the flora and fauna of Middle-Earth, inspired by the Medieval text “Maxims II” that appears in the Exeter book.[8] It presents a hierarchy of nature that has dissolved and is now upset by the mechanization of Orthanc. The tone of appreciation that the Ent has towards the careful relationship between the races that inhabit Middle-Earth and the natural world implies a possible peace found in balance and respect for the boundaries of each species, each devoted to its craft and role.

“Ent the earthborn, old as mountains;

Man the mortal, master of horses:[…]

Hound is hungry, hare is fearful…”.[9]

The message that seems to stem from the poem is that a collaborative and peaceful relationship with nature has respect for its boundaries at the forefront – the ability not to control and engineer it, but to bestow to each species and community with the freedom to develop in the role that has naturally been assigned to it. The importance of this message not only on our own efforts for having a less conflictive relationship with nature, but also for any peacebuilding efforts, is not lost. The first step of peacebuilding comes with respect for the customs and traditions of each party affected by a relationship, and an understanding of where boundaries are necessary to allow each group to have the freedom to exist undisturbed.

However, Ents ultimately become a secondary voice in the overarching story of the War of the Ring, eclipsed by the great deeds of human heroes and large battles. With their dwindling role in the story, the Lord of the Rings is giving yet another message, intentional or not, on the marginalization of nature in our understanding and consideration of conflict. The conflict of the mechanical world against the natural one, although it seems the most pervasive and inevitable of the ones present in the overarching history of Middle-Earth, is glossed over and ultimately ignored, leaving the fate of the Ents unwritten and darkly uncertain.

Myth and fantasy, by giving a face and a voice to ideas that might only exist as a nebulous concept in the minds of many, have the power to elicit real change. They reflect our relationship with the world, offer criticism as well as insights, and inspire others to see the value in the beauty that only some see. Most importantly, they generate empathy and understanding, essential elements to work toward peace. Stories tell us much about our relationship to the natural world, and how far away we still are from achieving a long-lasting peace with it. All other conflicts are sub-edited to this one, intrinsic to the survival of all of us. It only takes listening to the unheard voices, and caring about that which does not cry out to be cared for. In the words of Treebeard:

‘I am not altogether on anybody’s side, because nobody is altogether on my side, if you understand me: nobody cares for the woods as I care for them.’[10]

What do you think?

- What different lessons about conflict, peace and peacebuilding do you think that Tolkien’s Ents can teach us?

- Besides the Ents, what other elements of Tolkien’s works offer readers the chance to think about peace and peacebuilding?

- What kinds of conflict resolution do Tolkien’s works – and their later adaptations – particularly promote?

- Can you think of other myths that explore harmony and conflict between humans and the environment?

- What role can/does fantasy play in shaping how we think about peace and approach peacebuilding?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy ‘Active Hope in the Climate Crisis‘, ‘Jim Bendell’s Climate Doomism‘, ‘Peace in Disney’s Fairy Tales‘, ‘The Shield of Achilles‘, and ‘Trauma, Peace and the Cabinet of Dr Caligari‘.

Albert Surinach I Campos, December 2023

Further reading

- Buchan, Bruce. “Explaining War and Peace: Kant and Liberal IR Theory.” Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, vol. 27, no. 4, 2002, pp. 407–28.

- Gerwin, Martin. “PEACE, HONESTY, AND CONSENT: A HOBBESIAN DEFINITION OF ‘PEACE.’” Peace Research, vol. 23, no. 2/3, 1991, pp. 75–85.

- Lee, Stuart D. “The Keys of Middle-Earth. Discovering Medieval literature through the Fiction of J.R.R.Tolkien.” 2005. Palgrave Macmillan.

- RAAFLAUB, KURT A. “Conceptualizing and Theorizing Peace in Ancient Greece.” Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974-), vol. 139, no. 2, 2009, pp. 225–50.

- Shippey, Tom (2001). J. R. R. Tolkien – Author of the Century. Houghton Mifflin.

- Sutter, Paul S. “The World with Us: The State of American Environmental History.” The Journal of American History, vol. 100, no. 1, 2013, pp. 94–119.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (John Ronald Reuel), 1892-1973. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien : a Selection. Boston:Houghton Mifflin Co., 2000.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. Edited by Christopher Tolkien. 1977. The Silmarillion. George Allen & Unwin Ltd.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. The Two Towers. HarperCollins, 2005.

[1] Tolkien, Letters, 254.

[2] Buchan, 409.

[3] Gerwin, 78.

[4] Raaflaub, 229.

[5] Sutter, 97.

[6] Shippey, 88.

[7] Tolkien, Silmarillion, 62.

[8] Lee, 183.

[9] Tolkien, The Two Towers, 77.

[10] Tolkien, The Two Towers, 74.