Du musst Caligari werden. (‘You must become Caligari.’)

Fittingly, perhaps, accounts of the production and reception of Robert Wiene’s 1920 silent horror film The Cabinet of Dr Caligari are often contradictory and unclear. Set workers told conflicting stories;1 the film’s reception by critics was apparently both positive and negative;2 and even the writers’ intentions remain unclear.3 The Expressionist elements which have made the film so famous today were almost entirely the work of set designers Hermann Warm, Walter Reimann, and Walter Rohrig.4 The film was released abroad just as bans, both official and unofficial, on German films and other products were being lifted both in Europe and America, making the film a relative success abroad (though, again, exactly how successful it was is still debated by scholars).

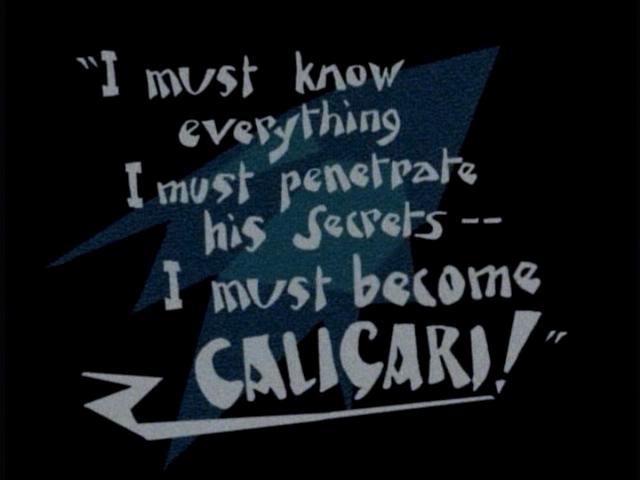

The film itself tells the story of a hypnotist whose carnival act, a somnambulist named Cesare, tells the future of various spectators, including a young man named Alan, who is found murdered at the exact time Cesare predicts. This leads Alan’s best friend, Francis, to begin an investigation, during which his fiancée is kidnapped by Cesare and Francis discovers the mysterious hypnotist is also the director of a mental asylum. In a twist at the end, we learn that Francis has been a patient in the mental asylum, alongside both his fiancée and Cesare, which Caligari runs.

Hans Janowitz and Carl Mayer, the film’s two writers, met in the months following World War I, both harbouring a deep sense of bitterness and strongly committed to pacifism in the wake of the war. The two came from wholly different backgrounds: Janowitz had been an officer in the German army5 while Mayer had faked insanity to escape military service.6

Analyses of the film have naturally focused on what its creators were trying to articulate about war and its aftermath. Anton Keas argues that the tall, imposing look of the hand-painted sets reminds audiences of trenches, and the somnambulist Cesare’s blind willingness to follow orders likens him to a good soldier in the war that had ended just a year before the film’s release. Additionally, Cesare’s tendency to kill at dawn may be a reference to the fact that many battles began at dawn during the war,7 or that soldiers guilty of desertion were supposedly often shot at dawn. In the years since the film’s release, it has been labelled as the first modern horror film,8 and much scholarship has been devoted to the film’s anti-war sentiments, whether those were intentional on the part of the writers or not.

With all these allusions and interpretations in mind, the film poses an interesting paradox: a story which many argue is about war includes no explicit reference to it and is set during a period of peace. In fact, the film begins as a carnival comes to town, drawing the attention and excitement of its three main characters, among many others. The film is bookended by scenes taking place in a mental institution, which became increasingly common as many soldiers returned from the war with newly recognized symptoms of PTSD; but the film makes no explicit reference to patients of this kind. In some ways, then, there is a disjunction between the world of the film (as a place seemingly untouched by war) and the background of its writers (men traumatised by war).

What do you think?

- When does war end and peace begin? What traces of war (e.g. PTSD) flow over into more peaceful times, and do we always recognise them as legacies of war?

- Should war and peace be considered binaries? Or phenomena that overlap? Should they be defined exclusively in opposition to each other?

- What role can films play in prompting critical reflection on war and its effects? And on how people experience post-conflict peace/life?

- Is this film ‘anti-war’? In what ways could it be described as pacifist?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy ‘Frankenstein in Baghdad‘, ‘The Magnus Archives‘, ‘Journey for Forgiveness‘ and other items with the tag ‘Elusive Peace‘.

Arden Henley, May 2022

1 John D. Barlow, German Expressionist Film (Boston: Twayne, 1982), p. 34.

2 Anton Keas, ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’: Expressionism and Cinema” (Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press, 2006). For further reading, see also: Anton Keas, “The Cabinet of Dr Caligari: Expressionism and cinema”; Armstrong, Gordon S. “Political and Practical Ideologies.” Performing Arts Journal 15, no. 1 (1993): 38–41; Budd, Mike. “The National Board of Review and the Early Art Cinema in New York: ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ as Affirmative Culture.” Cinema Journal 26, no. 1 (1986): 3–18; Cardullo, Bert. “Art-House Cinema, Avant-Garde Film, and Dramatic Modernism.” The Journal of Aesthetic Education 45, no. 2 (2011): 1–16; Robinson, David. Das Cabinet Des Dr. Caligari (London: British Film Institute, 1997); Schrader, Paul. “PRODUCTION DESIGN.” Film Comment 52, no. 2 (2016): 58–60.

3 Barlow p. 29 and 33.

4 Ibid., p. 33.

5 Cornelius Partsch and Damon O. Rarick, Translators note to excerpts from Jazz by Hans Janowitz (Bonn: Wiedle, 1999). http://cat.middlebury.edu/~nereview/25-1-2/Janowitz.html.

6 Barlow p. 32.

7 Keas p. 41-59.

8 Roger Ebert, ”A world slanted at sharp angles,” Rogerebert.com, 3 June 2009, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-the-cabinet-of-dr-caligari-1920.