How would you describe the landscape of peace?

The landscape of war, propagated by history books and news media, haunts the social imaginary with images of defense infrastructure, environmental destruction, and mass human casualty. As with more insidious forms of conflict, the practice of visualizing peace exists on the periphery of collective consciousness. Although peace is elusive, it does, like all activity, materialize in space, whether that be in an imagined utopia or your own backyard. So, when you visualize peace, you are also visualizing place. As part of the Visualising Peace Project, we set out to explore how a more explicitly place-based dialogue on peace might empower individuals and communities to embrace the peacebuilding potential of their placemaking practices.

Our research has highlighted the extent to which place is a socially constructed phenomenon. I like to explain the concept of place like this: a place is distinct from a space in the same way a home is distinct from a house. Unlike flora, fauna, or physical architecture, sense of place cannot be empirically identified. Rather, our sense of place is a composite image that develops in our mind over time, layers of memory, culture, history etc., that overlay, but are not bound to, a landscape. Therefore, the physical landscape itself, whether it be a lush forest or an inhospitable slum, generates a heterogenous pool of ‘place images’ that visualize peace differently. This makes sense when you consider that the familiar voices, objects, and memories that transform a house into a home for its inhabitants would not bring a stranger a deep-seated sense of peace and belonging upon entering the same space for the first time.

Sense of place is not a stable construct, and it continuously regenerates as we experience new places, meet new people, and learn new things. The term ‘placemaking’ encompasses all the practices that regenerate this ‘place image’. However, institutional placemaking interventions often overlook the organic process by which place is imagined, experienced and continuously remade within communities. Instead, they opt for progressive design solutions born from the sustainable development discourse (for case studies check out my posts on the 15-Minute City and Neom). For example, the park is a normative typology for placemaking, but if we were to insert a generic park in every community in the world, we would obscure the intricate web of relations that already constitutes that place, reproducing spatial injustice. In a hypothetical community, a park might be visualized as a microcosmic ecotopia, fostering children’s appreciation of nature, and facilitating community gatherings, but sense of place is as much about what you see as what you don’t. What places have been levelled for the development of this urban greenspace? How has this intervention transformed the socioeconomic makeup of the neighborhood, kick-starting gentrification? This is not to say that placemaking initiatives are bad by any means, but that placemaking (as is self-evident in the name) should be focused on the process of making, and the opportunity it provides for amplifying underrepresented voices, addressing community needs, and encouraging civic engagement and care for one’s environment. So, the question we need to ask is: how can placemaking be reformulated as a contextual and democratic peacebuilding framework?

To answer this question, we organized a focus group of participants from the University of St Andrews to consider how encouraging individuals to visualize place might build community capacity for visualizing peace. The focus group consisted of two drawing-based activities that challenged participants to respond creatively to the following tasks:

1. Visualize your sense of place in St Andrews.

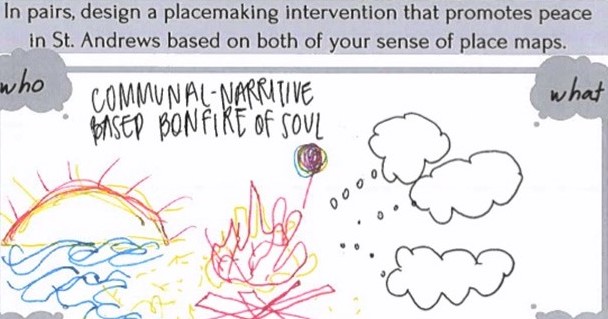

2. In pairs, design a placemaking intervention that promotes peace in St Andrews based on your sense of place maps.

This focus group used ‘sense of place map’ instead of ‘place image’ to underscore the relationality of place and to encourage participants to move beyond conventional landscape scenes or geographically accurate maps in their representation of place. We designed the explanatory segments of the focus group, consisting of video excerpts, thought-provoking quotes, and open-ended questions, to get participants thinking critically about the relationship between peace and place, without overly prescribing their approach to the focus group activities. The first activity asked participants to visualize their sense of place in St Andrews without drawing a geographical map. We encouraged participants to reflect on their personal sense of place, rather than defaulting to spaces, activities, and images commonly associated with peace. To be sure, normative peace imagery, like hearts, trees, and flowers, did feature heavily, but they were ambiguous signifiers in larger webs of meaning that were unique to each individual.

Our Findings

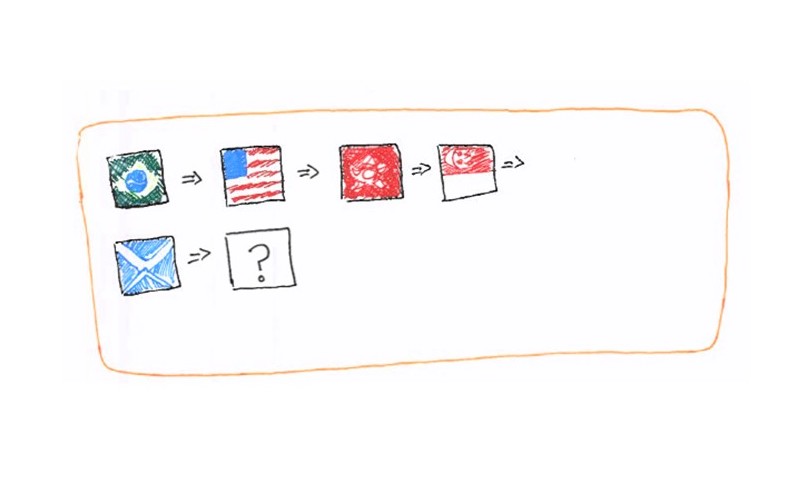

When we surveyed the participants at the beginning of the focus group about what place means to them, a physical location was the most common response, so it is compelling that the ‘sense of place maps’, created later in the focus group, challenge this common definition of place by stretching across space and time. Not only did some participants include places distant from St Andrews, e.g., a drawing of five national flags with arrows to denote the participant’s movement between countries, but others depicted the act of moving across space itself in airplanes, cars, or boats. The inclusion of forms of communication in some drawings also demonstrates the complex relationship between sense of place and physical space. One drawing includes an outgoing facetime call, a few others include speech/text bubbles, some of which use languages other than English. The importance of relationality to one’s sense of place, even though relationships are not contingent on long-term proximity (especially with contemporary communication technology), challenges the notion of place as a delineated space. The direction of our research was informed by the influential short essay, ‘A Global Sense of Place‘, by geographer Doreen Massey, which argues that places are the nodes of a constructed network of relations which span across the globe. To observe this radical conception of place in the participants’ handling of space was very exciting. It supports our hypothesis that sense of place is not a new approach to peacebuilding, but a fundamental human activity that provides individuals with a sense of peace as they move through – and experience a sense of place in – different environments.

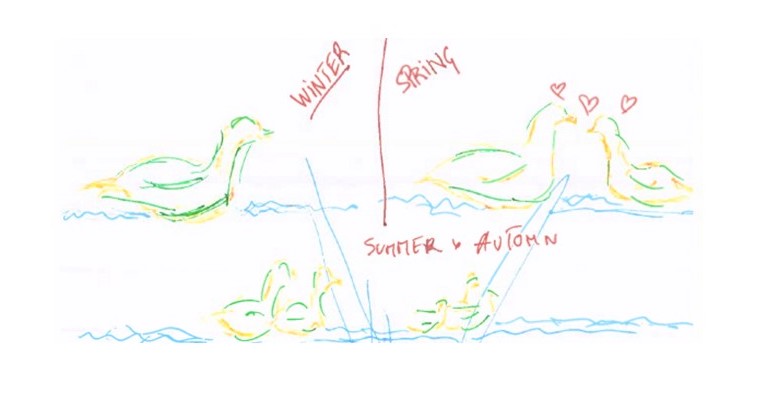

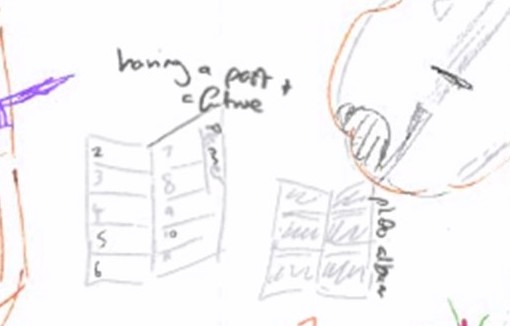

The cycle of life was a common theme across the drawings, which suggests that an awareness of the passage of time factors into how individuals visualize place. For example, one drawing has three images, the first labeled “winter,” the second “spring,” and the third, “summer+autumn.” The first image shows a single duck, the second, two ducks surrounded by hearts, and the third, the duck couple following a brood of ducklings. Here, place is not visualized as a peaceful landscape dotted with ducks, but as the natural forces that continuously transform this landscape, regenerating life, and thus crafting narratives that are not about a place, but constitute the place itself and the joy a person takes in feeling a sense of place. Another drawing shows a photo album with the caption “past” and a planner with the caption “present.” Again, the importance of temporality to one’s sense of place is highlighted by these two sketches, as humans commonly use both formats to make sense of their life and how it has unfolded across space and time. Furthermore, a photo album and a planner together consolidate one’s past and future for consumption in the present. In essence, each format is a place image of sorts. These insights are valuable because they demonstrate that despite the specificity of each drawing, the life experiences depicted are really part of a shared human experience. The spatial narratives crafted by the participants suggest that visualizing place can become be a powerful peacebuilding tool, as it allows communities to celebrate individuality and shared humanity.

In the second half of the focus group, we asked participants to design a placemaking intervention in small groups that would promote peace in St Andrews. We urged groups to develop their peacebuilding intervention from the group’s set of “sense of place maps,” rather than normative models for peaceful community living. This activity was designed to encourage groups to think about how their shared human experience, brought to light in their reflections on place, could be used to build community peace, while also giving participants the opportunity to discuss how their conceptions of place-based peace differ from one another.

All six proposals designed were communal and encouraged human and environmental connection to occur organically. One group came up with a walk through the town of St Andrews that people could join for conversation or silent reflection. They recognized that some people gain a sense of peace from talking with others, while others feel at peace in solitude. To accommodate these different needs in a community-building activity their intervention encourages “splitting up, [and] coming back together” throughout the walk. Another group proposed a “communal-narrative based bonfire of soul” on the beach where community members could enjoy the sunset and exchange stories. This intervention emerged from the importance of connection with nature, narrative, and positive sensory experience in the group’s “sense of place maps.” Most of the proposals were experiences rather than new architecture (those that involved a physical structure were flexible and collaborative). Thus, they all used pre-existing means of placemaking drawn from their unique combination of sense of place maps. By letting the participants have placemaking authority, this activity was a microcosm of a place-based, democratic, and organic, peacebuilding process. The focus group was small and was not representative of the St. Andrews community as a whole. On a larger scale, and with more diverse understandings of peace and place, the process of collaborative placemaking is usually more difficult. However, the focus group was valuable to our research since it suggested that place is a good place to start when visualizing peace.

What do you think?

- Can you think of three places where you feel at peace? Do they have anything in common?

- Have the places where you feel at peace changed over time? If so, why?

- Look through your camera roll. What image best represents the word home to you?

- Draw a ‘sense of place map’. Does your drawing have similar themes to the examples discussed in this blog post?

- What relationship can you see between personal placemaking and peacebuilding?

- What advantage can we take of the relationship between placemaking and peacebuilding in local communities and post-conflict reconstruction?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy Arcosanti, The 15-minute City, The LINE in NEOM, The Experimental City, The Invisible Urbicide Project and Peace as Transcendence.

Eleni Spiliotes, April 2023

References

- https://vpp.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2023/04/15/peace-and-place-2/

- Massey’s theory of place as a socially constructed phenomenon: https://eclass.hua.gr/modules/document/file.php/GEO272/MASSEY%20-%20a%20global%20sense%20of%20place.pdf

- Great blog about place studies: https://www.placeness.com/

- Podcast on place and care ethics: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/juliet-davis-care-urban-design-and-the-city/id1588790585?i=1000581725045

- Project for Public Spaces website: https://www.pps.org/