Trigger warnings: blood, body horror, self-harm, suicide

‘When I was a boy, my dog crawled out onto the porch to die. Before the end it yelped, as if it had seen something real.’

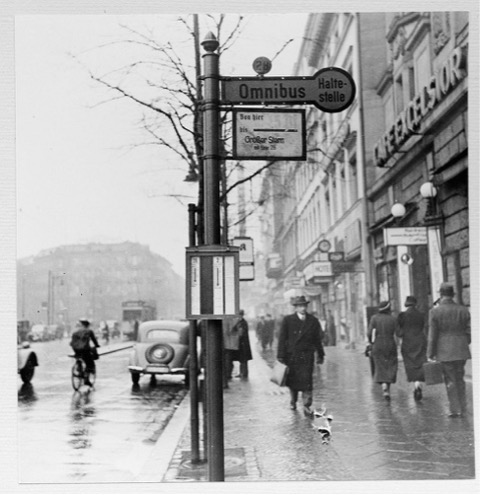

Possession is a 1981 arthouse horror film directed by Andrzej Zulawski. The film follows Mark, a Cold War spy, who returns home to find his wife, Anna, asking for a divorce and acting increasingly erratically. The film is a uniquely transnational one, filmed in West Berlin by a Polish director and featuring actors from Germany, France, England, America, and New Zealand. The film features Isabelle Adjani as Anna and Sam Neill as Mark. Director Andrzej Zulawski, who also wrote the film, based it on his own divorce, and some scenes from the film are taken directly from Zulawski’s experience.

Themes of mistrust, suspicion, and paranoia dominate the film and the relationship between the two main characters. Mark, upon hearing that Anna wants a divorce, almost immediately suspects her of infidelity, and he spends the first hour of the film following and watching Anna, tracking down and beating her suspected lovers, and even hiring a private detective to follow her. When he isn’t keeping tabs on her, Mark is rocking erratically in a rocking chair, screaming at his wife, and, as Maitland McDonagh puts it, ‘[having] a feature-length nervous breakdown.’

There are sinister tones throughout. Mark has a reason to be suspicious of Anna if her actions in the film–injuring young girls in a ballet class, smashing milk bottles, and cutting her own neck with an electric knife–are anything to go off. Most of the film is shot using a handheld camera, giving it an off-putting and dizzying feel. The film is in turns grey-scale and vibrantly colorful, alternately eerily calm and gratuitously violent. This uncanny, oscillating atmosphere gives the film a more unmoored and universal feel. Whereas characters in other horror films make easy, avoidable mistakes–walking uninvited into strangers’ houses, playing with Ouija boards, splitting off from the group while in a haunted location–this film has a much bleaker moral: this could happen to you, and unless you pay attention, you won’t see it coming.

The decision to shoot the film in West Berlin, an area which exemplified the dangers of Cold War attitudes, is an interesting one. Mark and Anna are in one sense a sort of microcosm of the East/West divide: there is mutual suspicion and mistrust, as detailed above, and this mistrust leads to a breakdown in their relationship and a staggering amount of violence, the more memorable parts of it self-inflicted. While depicting the couple’s violence, the film keeps a steady focus on their son, Bob, and how the relationship and its breakdown will affect him. In this East/West metaphor, Bob represents the world to come: young and learning how to live in the post-conflict era, and probably unable to synthesize a world without violence in it. The political stakes here are clearly set: a present world of mistrust and violence leads to an unpredictable, terrifying world to come.

The film does not present a positive outlook on Bob’s future: love throughout this film is equated with violence. When Anna, midway through an argument, cuts her own neck with an electric knife, Mark takes it from her and, as a bizarre apology and acknowledgement of his own guilt, begins to cut his arm with it. The couple spend most of the film alternately throwing each other around their apartment and feeling self-destructively guilty over it. The effect this has on Bob is clear. In a scene where Mark comes home to find Anna has left Bob at home alone for hours, the child has taken a jar of jam and spread it over the walls and himself. The jam looks disturbingly like blood, and the implication is clear: Bob has taken something so mundane and homely as a jar of jam and made it into an image of violence. The lessons Bob has learned from watching his parents promote deeply problematic, disfunctional approaches to conflict resolution; he does not have the tools for reconciliation, or to create peace in his own life, but he is fast learning how to become just as erratic and violent as his parents. The film, rather than promoting an image of love and peaceful relationships, dwells on the consequences of their lack: the beginning of yet another cycle of suspicion, noncommunication, and violence. In that sense, it represents a stark warning – with family-based horror reflected onto wider political conditions. Through Bob, we look bleakly into a future based on escalating tensions and violence, and we are meant to be frightened above all by what could come in his lifetime, what havoc he himself may wreak.

What do you think?

- What impact can explorations of the absence of peace and negative forms of conflict resolution have in helping us to visualise peace?

- What effect does violence have on young children? And is it right or meaningful to draw on the microcosm of family life to offer wider political commentary and predictions?

- What role can the genre of horror play in helping us wrestle with topics such as war and peace?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy The Magnus Archives, Frankenstein in Baghdad, Unlearning War, How do children visualize ‘Life After Conflict’?, and ‘Jasmine’ by Nora Nadjarian.

Arden Henley, 2022

Alison Taylor, “Chapter 3: Up the Spiral Staircase” in Possession (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2022), pp. 49-80.

Allison Taylor, interview with Ariel Baska, Ride the Omnibus, podcast audio, 12 October, 2020, https://anchor.fm/omnibusride/episodes/Possession-1981-ekuacq/a-a3h0354.