Trigger warning: descriptions of gore, body parts, corpses

‘I wanted to hand him over to the forensics department, because it was a complete corpse that had been left in the streets like trash. It’s a human being, guys, a person,’ he told them.

‘But it wasn’t a complete corpse. You made it complete,’ someone objected.

‘I made it complete so it wouldn’t be treated as trash, so it would be respected like other dead people and given a proper burial,’ Hadi explained.

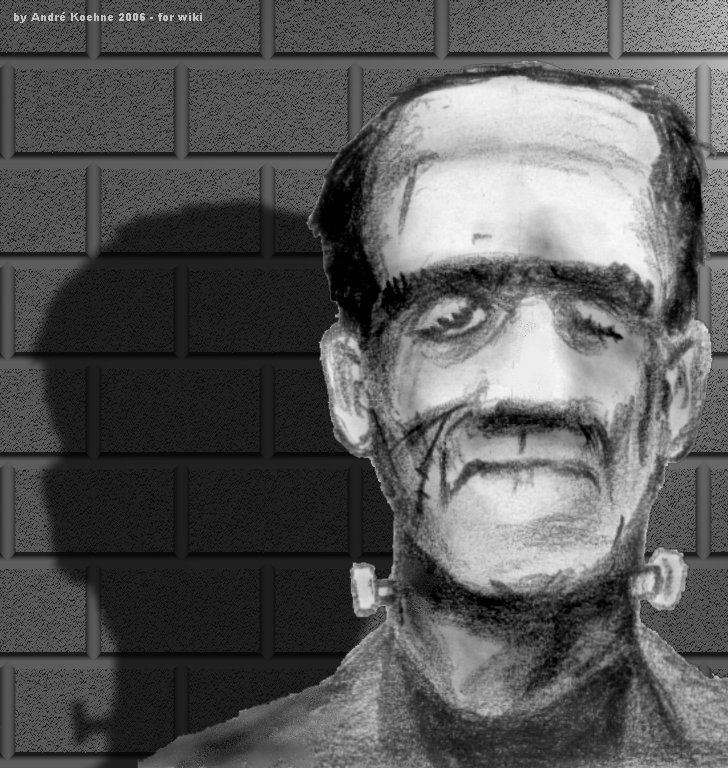

Frankenstein in Baghdad, by Ahmed Saadawi

Ahmed Saadawi, an author, poet, and filmmaker, was raised in Baghdad and continues to live there with his wife and children. He had served in the Iraqi army three times by the time of the US occupation in 2003 and has been publishing his work since 2000. His novel Frankenstein in Baghdad won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2014 as well as the Grand prix de l’Imaginaire in 2017. Although published in 2013, Frankenstein in Baghdad takes place immediately after the US invasion of Iraq ten years earlier. In the novel, Hadi al-Attag, a junk dealer in Baghdad, collects the body parts of bomb victims and stitches them together to create a single body, intending to give these bomb victims a proper burial. However, when he completes the body, the spirit of another victim possesses it and demands revenge. The novel becomes an allegory for the US invasion, calling the invaders’ motivations and intentions into question.

Saadawi’s novel presents an indictment of the US’s presence in Iraq and in the Middle East more generally through the vehicle of a story Western audiences know well: Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. In Saadawi’s version, the mad scientist is replaced by a man making a meagre living in a small apartment in Baghdad; and the monstrous life force which reanimates the body is not Gothic science so much as a freak spiritual accident. This body, who Hadi has named the Whatsitsname in acknowledgement of the fact that many of the victims whose body parts he has scavenged will never be identified or given a burial, seeks revenge on each of the bombers responsible for creating one of his body parts. What starts out as an already well-known plot of bloody revenge quickly spirals even further out of control as the body parts on the Whatsitsname begin to rot and he must find “innocent” flesh to replace it to complete his act of vengeance. Thus the Whatsitsname, under the guise of exacting revenge, begins to kill innocent civilians in a brilliant, visceral allegory for the US’s ‘war on terror’ in the wake of the 9/11 attacks.[1]

In the midst of this allegory, Saadawi also subtly depicts pockets of peace. The most poignant of these is the story of Elishva, an old woman grieving the death of her son who believes that the Whatsitsname is that son returned to her. She inspires in the Whatsitsname some compassion and mercy for the first time in the novel. Thus, while condemning the actions of the US government (which were supposedly rooted in ‘justice’ and designed to prevent further conflict – but exposed here as violent revenge that gets quickly out of control), Saadawi advocates for a more small-scale, empathetic form of peace-making based on human connection and compassion.

These pockets of peacebuilding are not enough in the face of corruption and a violent, unjust war, however. In the novel’s conclusion Hadi is arrested for being the Whatsitsname and many, including Elishva, flee Baghdad. In an ultimately bleak ending, the reader must come to terms with Saadawi’s insistence that small-scale peacebuilding, while fundamental in creating larger peace, is sometimes still insufficient. Elshiva finds small pockets of peace when she speaks on the phone to her daughters who no longer live in Baghdad, but these are presented as both fleeting and delusional: ‘With her veined and wrinkled hand, Elishva would put the Nokia phone to her ear. Upon hearing her daughters’ voices, the darkness would lift and she would feel at peace. If she had gone straight back to Tayaran Square, she would have found that everything was calm, just as she had left it in the morning. The sidewalks would be clean and the cars that had caught fire would have been towed away.’ The only way that Elshiva finds lasting peace in the end is by leaving Baghdad far behind and going to a part of the world that has not known this kind of conflict.

What struck me most in this novel was the blend of horror, science fiction, and realist political messaging. Saadawi plays on both a familiar horror story–Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein–and on the fantastical elements of his own devising to formulate a metaphor for the Iraq war that is simultaneously so divorced from and so tied up in its real-life inspiration. Saadawi visualises peace in this novel through individual means, whether that is through Elishva’s befriending of the Whatsitsname, Hadi’s insistence on the Whatsitsname’s humanity (at least in the beginning of the novel), or the care and compassion of Elshiva’s daughters who help their mother to find moments of inner peace by humouring her delusions. He also raises important questions about the role played by the quest for justice – or revenge – in processing trauma and resolving (or driving) conflict. Different methods for finding peace or closure meet with different results, and in many ways the novel depicts a nightmare cycle of violence that one can only escape by stepping right out of it. Some ‘solutions’ end up perpetuating the problem. By creating a monster both familiar and strange, Saadawi allows us to appreciate the horror of the story itself alongside some very real political condemnation and reflections for the future.

What do you think?

- What different methods of achieving peace does Frankenstein in Baghdad get you thinking about? Does it promote some methods over others?

- Does this novel suggest that acts of ‘healing’ or attempts to achieve justice can end up resulting in yet more violence? What implications does this have for different kinds of peace-building?

- What role can individuals unwittingly play in perpetuating violence compared with the role played by politicians or military forces?

- What does this novel tell us about the necessary conditions for lasting, sustainable peace compared with a cycle of violence?

- Is delusional peace (like Elshiva’s pockets of peace when mistaking the Whatsitsname for her lost son) just as valuable or healing for someone experiencing trauma as peace founded on something more real?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy ‘The Magnus Archives‘, ‘Achilles in Vietnam‘, Make me a Channel of your Peace‘ and items with the tag ‘Pockets of Peace‘.

Arden Henley, May 2022

[1] For reviews and analysis see, e.g., Murphy, Sinéad. “Frankenstein in Baghdad: Human Conditions, or Conditions of Being Human.” Science Fiction Studies 45, no. 2 (2018): 273–88. https://doi.org/10.5621/sciefictstud.45.2.0273; Bizawe, Eyal Sagui. “Arab Sci-Fi Novel ‘Frankenstein in Baghdad’ Embodies All That’s Evil in Modern-Day Iraq,” Haaretz, 8 August 2017, https://www.haaretz.com/life/books/.premium.MAGAZINE-frankenstein-in-baghdad-embodies-all-that-s-evil-in-iraq-1.5440860; Haytham Bahoora, Writing the Dismembered Nation: The aesthetics of horror in Iraqi novels of war; and https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/feb/16/frankenstein-in-baghdad-by-ahmed-saadawi-review. For an overview of the Iraq War, see e.g., Fawcett, Louise. “The Iraq War Ten Years on: Assessing the Fallout.” International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-) 89, no. 2 (2013): 325–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23473539.