They are coming! they are coming!

Alak! an’ wae’s me!

Though the sword be in the hand,

Yet the tear’s in the e’e.Is there blood in the moorlands

Where the wild burnies rin?

Where the wild burnies rin?

Wind reid down the lin?O billy, dear billy,

James Hogg, The Brownie of Bodsbeck

Your boding let be,

For it’s nought but the reid lift

That dazzles your e’e.

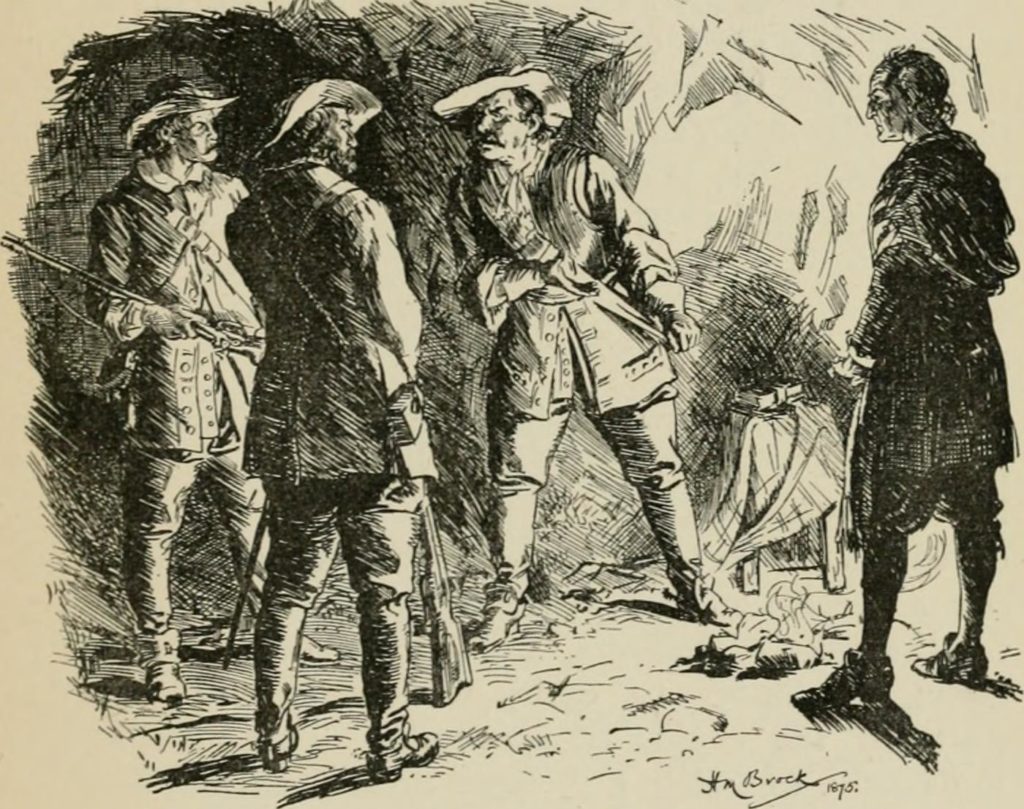

James Hogg’s The Brownie of Bodsbeck concerns a period of Scottish history sometimes referred to as ‘The Killing Time’, during the period immediately prior to the revolution of 1688, when Presbyterianism was suppressed by the Stuart authorities. Unable to meet in churches, committed Presbyterians would take part in secret, illegal open-air services. Some, most prominently the radical group known as the Covenanters, lived as outlaws in violent conflict with the state.[1] Brownie depicts the persecution of a group of Covenanters under the Laird of Claverhouse, referred to as ‘Clavers’.

The most remarkable aspect of the text is its highly sympathetic rendering of the Covenanters and its condemnation of the Stuart authorities, in contradiction to the established opinion of the time among Scotland’s literary elite – including, notably, Hogg’s friend Walter Scott, who had written his own book on the subject, Old Mortality. This difference in opinion stemmed primarily from Hogg’s grounding in the oral historic tradition of his native Ettrick, in the Borders, where the Covenanters were remembered as defenders of freedom of religion against authoritarian state interference.[2] Hogg thus prioritises a vernacular, marginalised narrative of the Scottish 1680s.

In the novel, the fugitive Covenanters, living in hiding, are often mistaken for brownies, mythical creatures also prominent in the folklore of the Borders who were believed to help those they favoured by working for them in secret. When the Covenanters assist the farmer Walter Laidlaw with the harvest in exchange for sheltering them, the community in general attributes it to the ‘Brownie of Bodsbeck’. Sharon Alker and Holly Faith Nelson argue that not only is Hogg’s treatment of the Covenanters a social commentary in support of the working class as against the largely Episcopalian aristocracy, but that the Covenanters constitute an ‘alternative community’ independent of the orthodox social hierarchy, a radical re-imagining of the potentialities of Scottish society.[3]

With the importance of everyday and vernacular narratives increasingly emphasised in modern peacebuilding, The Brownie of Bodsbeck will make an important comparison for those who work in the field as an alternative narrative of past conflict. Alternative renderings of different groups, that resist demonisation and move towards humanisation, are vital for visualising a peace more inclusive of the various communities and cultures involved in conflict. This text also reminds us of the role that literature (among many other media) can play in shifting intergroup contact towards more positive directions.

What do you think?

- Do our backgrounds (geographical, social, cultural, religious, economic, educational, etc) always determine how we categorise groups of people in war and peace? (For instance, might Hogg have taken a very different view of the Covenanters had he been brought up elsewhere?)

- What is to be gained from looking at a conflict and its combatants from alternative perspectives?

- How easy/difficult is it to try empathising with groups of people who have been depicted as ‘dangerous’, ‘wrong’, ‘other’, etc?

- How important to peace-making are diverse voices in our media, to offer different perspectives on ‘outgroups’?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy ‘The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner‘, ‘Intergroup Contact Theory‘. ‘Achilles in Vietnam‘ and ‘Journey: visualising peace through gaming‘.

Thomas Frost, December 2022

[1] Ryan K. Frace, “Religious Toleration in the Wake of Revolution: Scotland on the Eve of Enlightenment (1688–1710s)”, History 93, no. 3 (July 2008): 356.

[2] Douglas S. Mack, “Hogg’s Politics and the Presbyterian Tradition” in The Edinburgh Companion to James Hogg ed. Ian Duncan and Douglas S. Mack (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2012): 68-9.

[3] Sharon Alker and Holly Faith Nelson, “Hogg and Working-class Writing” in The Edinburgh Companion: 61-2.