“Listen. Listen to me.”

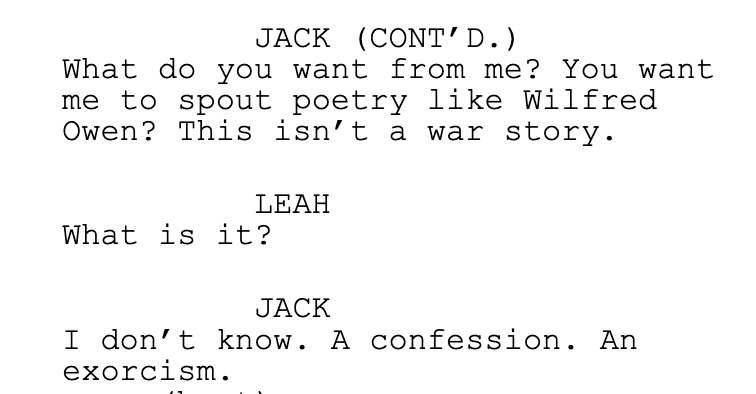

I am writing a series of screenplays, reflecting on different manifestations of peace. This particular story has gone through several iterations over the last three or four years, the most successful draft being as a 36-page script which I finished last April. I finally got the opportunity to shoot the concept as a film for the Visualising Peace project, but I have neither the time nor the budget to film all 36 pages (which would correspond to about 36 minutes of film in total). So the idea was boiled down to about 4 pages setting up the central problem (a ghost is haunting a man’s apartment) and the moral crux (he still hasn’t fully processed his friend’s death while at war).

The idea of a ghost haunting a group of old friends came from an article I had read several years ago. According to this article, a group of friends in a small Australian town was harassed by the ghost of what they deduced to be an old friend of theirs, who had died in a car accident several years earlier. The ghost had a habit of throwing small pebbles at the house, which is a detail I included in my story.

I set out to write a horror-comedy, with all the genre’s complexities and precarious balances intact. I am fascinated by the idea of horror and comedy as two sides of the same coin, and as someone who loves both genres and as a writer attempting to combine them, I have thought a lot about the concept – particularly how it can be deployed to help us think about peace. In many ways, both horror and comedy celebrate the proverbial Other, although they go about different ways of doing it: horror tends to present the Other as someone/something to be feared, whereas comedy usually makes the Other a more sympathetic character and encourages us to laugh with (not just at) them. The two genres share the kinds of tactics that well–horror novelist Stephen King wrote about, in reference to his own work: ‘I will try to horrify, and if I find I cannot horrify, I’ll go for the gross-out.’ In horror, if you cannot scare your viewer, gratuitous shots of blood and gore often do the trick; and in comedy, if you cannot shock the audience into laughter, a few well-placed fart jokes always go over well. Finally, both genres find ways to shift focus away from the conventional narrative and toward more secondary characters and their stories. For instance, both of the film students in The Blair Witch Project and Brian from Life of Brian surmount huge challenges, only to find that the story has not been about them at all, but about something else which we rarely, if ever, see onscreen (in the former, it’s the titular witch, and in the latter, it is Jesus himself).

On that last point: the film I wrote takes place entirely outside any of the conflicts it may discuss, and I did this for two reasons: practicality, which should be self-explanatory; and because I was inspired by the first chapter of Slaughterhouse-Five. The first few pages of this book are written from author Vonnegut’s perspective. In it, he describes speaking to a woman about the book he had decided to write while his daughter plays upstairs. She accuses him, and other authors of his day, of ‘pretend[ing] you were men instead of babies, and you’ll be played in the movies by Frank Sinatra and John Wayne or some of those other glamorous, war-loving, dirty old men. And war will look just wonderful, so we’ll have a lot more of them. And they’ll be fought by babies like the babies upstairs.’ I find myself coming back to that quote every time I see trailers for some new war film or statements from politicians about wherever they have committed more troops or equipment to a conflict. I have decided to heed this woman’s advice. The film I want to make is not about a war at all, but rather about the people on the outside who have done nothing wrong, who have lived domestic, peaceful lives, and become casualties anyway.

You can watch this short film by clicking on the link below:

What do you think?

- What do narratives of peace lose (or gain) by including representations of war?

- In what ways can horror as a genre help us look at peace and peace-building from new perspectives? Have you come across any works of horror where peace is a key theme?

- How can comedy help us understand peace and peace-building? Have you come across any comedy where peace is a key theme?

- What role does genre play in shaping how we respond to a narrative and what we take from it?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy ‘String Theory‘, ‘No Love Lost‘, ‘Dad’s Army‘, ‘The Magnus Archives‘ and ‘Frankenstein in Baghdad‘.

Arden Henley, December 2022