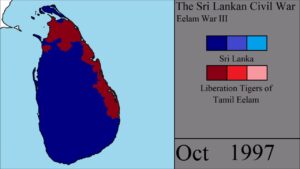

The Sri Lankan Civil War, officially spanning from 1983 to 2009, was fought between the separatist group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), who sought after an independent state for the Tamil ethnic minority group, and the Sinhala ethnic majority dominated government. The south of the island also simultaneously experienced violent insurrections by the radical and Marxist party Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP).1 The conflict garnered much attention from international actors and the 2002 ceasefire was hailed by contemporaries in the international stage as a landmark achievement for peacebuilding efforts everywhere. However, open hostilities resumed in 2006 and the country saw the rise of increasing ‘war for peace’ movements that labelled talks of ‘peace’ as unpatriotic and in support of interference by foreign actors. So how did Sri Lanka go from an example of successful peace talks to being hostile to even the word peace? What role did international actors play in this process and what limited the success of these actors?

The failure of international actors in building sustainable and lasting peace in Sri Lanka has been attributed to a number of domestic, historical and economic factors. For example, some critics of the peace process have pointed to the common bureaucratic hurdles faced by international actors in conflicts in securing funding as well as the inability to plan long-term in uncertain circumstances. Other critics, such as Oliver Walton, argue that in cases where international actors managed to secure the resources and means of implementation, the insufficient consideration of the local context by international donors lended counter-productive elements in the peace-building process.

One such ‘insufficient consideration’ that Walton points to was of the historic political structures. An example of this is the international support given to civil society organisations such as human rights activists and religious groups. Most international involvement in the peacebuilding process adopted the model of Liberal Peacebuilding. The international definition of civil society groups however failed to account for the local context on two grounds. The liberal peacebuilding approach adopted by many of the international actors involved in the peacebuilding process defined civil society groups as organisations that protect rights and promote democracy. This definition meant that some influential Sri Lankan civil society groups, historically formed across ethno-religious lines, were sidelined and underutilised as they did not have liberal democratic goals. Walton also points to the international definition of civil society organisations as non-state actors, ignoring the Sri Lankan context of a more fluid relationship2 between the centralised state and civil society organisations.3

Therefore, while international organisations tried to feed Sri Lankan civil society behaviour into their own model, given the interconnectedness of state and non-state actors, as well as the highly centralised and patronage-dependent political structure of the government, it may have been more effective to incorporate backing of civil society organisations through the government; for example, as Walton and Saranavattu propose, by funding organisations affiliated with the government. This may have also mitigated the hostile anti-international rhetoric and suspicion toward donor-backed civil society organisations following the ensuing of open hostilities.4 Another historical factor which the international approach could have adjusted for is the strong ethno-nationalist divisions present in Sri Lanka following independence from British colonial rule. The success of patriotic groups during and after the ceasefire period may suggest that if these groups were incorporated into the international peace approach, the threat of foreign backing may not have been as politicised.5

The international approach to peacekeeping also followed a top-down approach that prioritised ‘track-one negotiations’, or diplomacy between state officials and diplomats. This meant the exclusion of more inclusive processes that incorporated human rights issues.6 Representatives of Muslim minorities were not included, for instance;7 and the exclusion of the LTTE at the Washington donor conference was seen by some as contributing to their withdrawal from peace talks.8

The international framework, being based on a shared globalised understanding, familiarity with specific performance indicators, and expertise with technical English discourse, meant that a bulk of funding was directed at a small number of elites in the capital, Colombo. This preference for Colombo-based non-governmental organisations contributed to rifts between national and local NGOs, and undermined the popular legitimacy of civil society groups. This international understanding also had a specific idea of what peace looked like and labelled actors that voiced criticism of the peace process as inherently ‘anti-peace’. This restrictive discourse limited space for alternative, inclusive visions of peace, increasing tensions around marginalised groups often represented by civil society groups.

The lack of inclusion in the peacemaking process can be seen through international actors supporting the economic reforms of the UNP-led government. Supporting reforms strongly associated with one political group proved to be counterproductive given the polarised political space of the country. This is evident in the increased support for the JVP party and other Sinhala extremist groups.

Therefore, although the behaviour of international actors was influenced by a range of unique motives and backgrounds, the shared international framework that most international involvement functions in may not always be conducive to managing localised conflicts, and this suggests that there needs to be a larger push toward long-term contextualised and adaptive approach.

What do you think?

- How important is the international framework for peace, and can this be adapted to incorporate more local contexts?

- To what extent should international actors be involved in peace-building process?

- To what extent should the motives of international actors be more critically examined?

- How effective can international involvement be, given the short time frame that most actors are expected to deliver results in?

- How can differing economic and political ideologies of the international donor countries and the local state be reconciled for sustainable peace-building?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy Creating Peace in Post-Conflict Society: The use of Intergroup Contact Theory, and Colombia: The long road to peace.

Tao Yazaki, November 2023

- For the conflict in context: Frerks, Georg, and Mathijs van Leeuwen. “An Outline of the Conflict in Sri Lanka.” The Netherlands and Sri Lanka: Dutch Policies and Interventions with Regard to the Conflict in Sri Lanka. Clingendael Institute, 2004. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep05566.6. ↩︎

- pp.25 – 38, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/6033.pdf ↩︎

- Jonathan Goodhand & Oliver Walton (2009) The Limits of Liberal Peacebuilding? International Engagement in the Sri Lankan Peace Process, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 3:3, 303-323. ↩︎

- Höglund, Kristine, and Camilla Orjuela. “Hybrid Peace Governance and Illiberal Peacebuilding in Sri Lanka.” Global Governance 18, no. 1 (2012): 89–104. ↩︎

- https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/267269475.pdf ↩︎

- McGregor, Lorna. “BEYOND THE TIME AND SPACE OF PEACE TALKS: RE-APPROPRIATING THE PEACE PROCESS IN SRI LANKA.” International Journal of Peace Studies 11, no. 1 (2006): 39–57. https://www3.gmu.edu/programs/icar/ijps/vol11_1/11n1McGregor.pdf. ↩︎

- pp.15-16, https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/45a4af7f2.pdf ↩︎

- p. 6, https://www.cpalanka.org/wp-content/uploads/2007/8/view_peace_process_2002_2003.pdf ↩︎