Since 2013, the charity Never Such Innocence (NSI) has been giving children and young people a voice on conflict. Via an annual competition, schools workshops and high-profile roadshows, they provide opportunities for young people aged 9-18 to reflect on different aspects of conflict and conflict-resolution, and to share their views with politicians, policy-makers and other adults in influential, decision-making positions.

In 2022, their competition theme was ‘Life After Conflict’. They challenged children from all around the world to submit poetry, artworks, speeches and songs, reflecting on war’s impact and aftermath and on people’s efforts to find or build peace. 3181 children responded, from 96 different countries. You can explore all the winning entries here. I was privileged to help judge some of the entries and – with NSI’s permission – I have included a small sample in our museum because they have so much to teach us about how children visualise the myriad effects of conflict on many different people, and they also offer important insights on different forms of conflict resolution and peace-building, past and present.

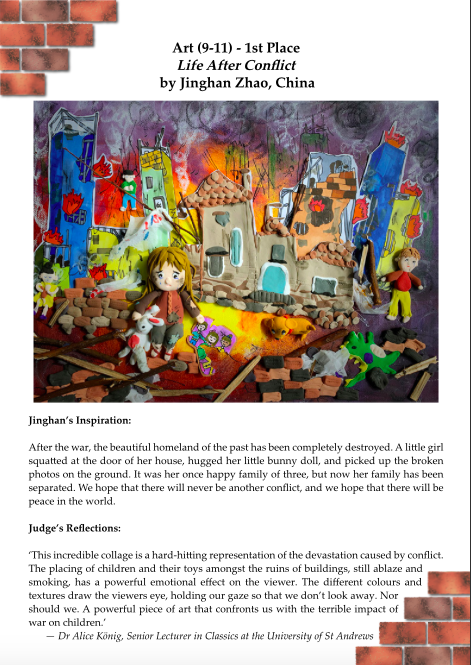

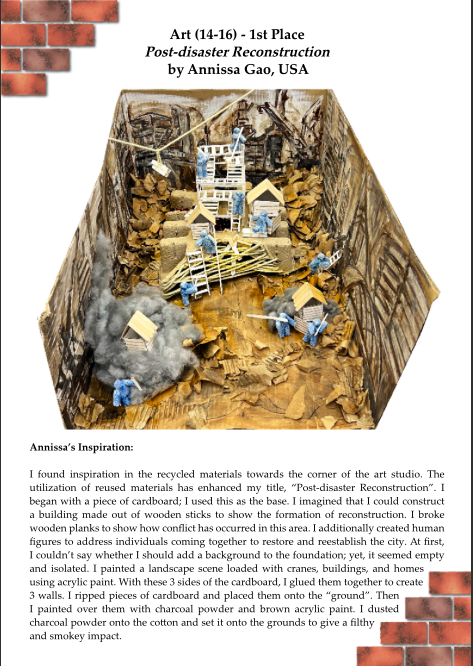

Some children focused on the immediate, physical costs of war: destroyed city-scapes, children trying to pick up the pieces of their lives in the debris, and the huge effort it takes to rebuild. Take, for example, this powerful collage (left) by Jinghan Zhao from China (aged 9-11) and the 3D paper sculpture by Annissa Gao from the US (aged 14-16):

Both speak to the chaos and material devastation that war wreaks. Jinghan’s collage focuses attention on the costs that children are made to bear, mental as well as physical: we see the wreck of childhood, not just buildings, in this blazing scene. Annissa’s piece, on the other hand, captures that period just after bombs have stopped falling when the momentum moves from destruction to reconstruction. The labour involved and the volume of debris in the scene are stark reminders of the material costs of war.

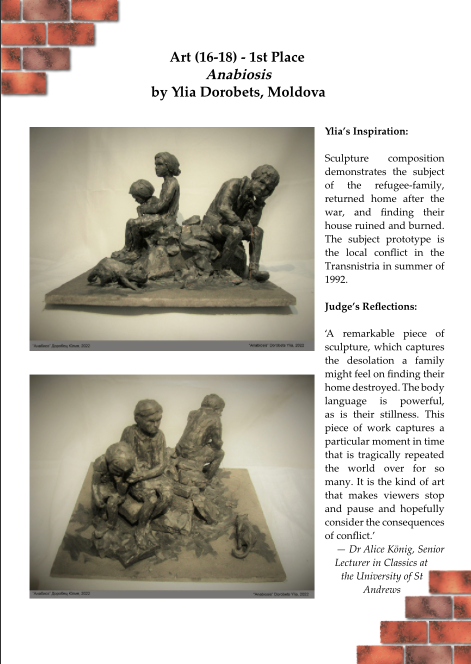

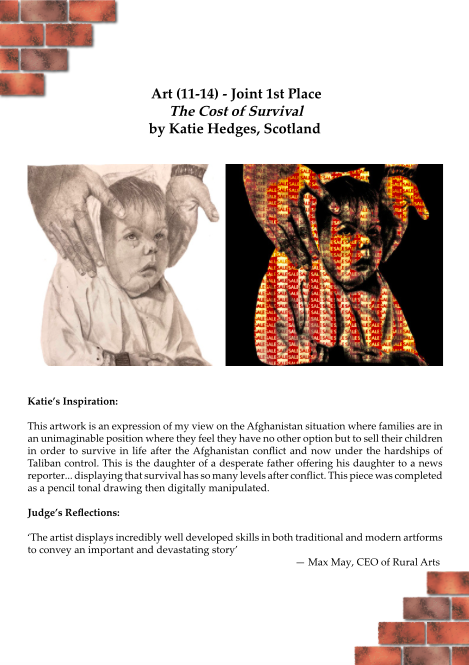

Other children focused more on the secondary impacts of conflict, such as displacement, economic hardship, famine and the vulnerability of children caught up in conflict to different forms of exploitation. Ylia Dorobets from Moldova (aged 16-18) used clay to capture the moment when a family realises that their home and all their belongings are lost. This sculpture invites reflection on a historic conflict (in Transnistria in 1992), but it also speaks to the experiences of many contemporary families all around the world. Equally ‘gut-punching’ was a pair of pencil drawings by Katie Hedges from Scotland (aged 11-14), reflecting the terrible post-conflict reality of many children in Afghanistan. The pencil drawing is breath-taking, and the shop-front aesthetics of the ‘sale’ version on the right confront viewers with a hard truth: that while we shop for ‘bargains’, others are forced by conflict to sell their own children to survive. Both are very hard-hitting works of art which capture the terrible costs of conflict, long after the guns stop firing, on young people and their families.

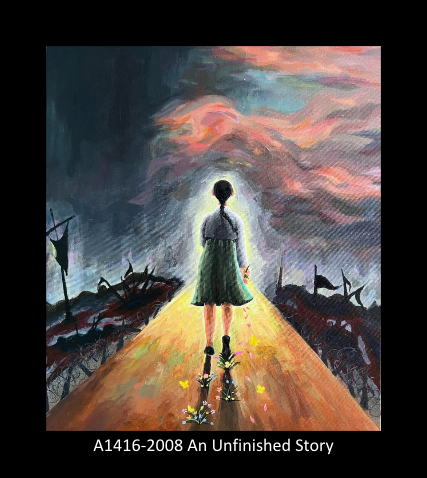

Several children reflected also on the legacy of sexual violence which many women and children suffer during times of conflict, and the long journeys they have to recover, seek justice and ‘make peace’ with what has happened to them. I was particularly struck by ‘An Unfinished Story’, which I read as a work of ‘artivism’ not just art.[1] It amplifies the experiences and voices of victims of sexual slavery, who have been telling their story and leading their own recovery – despite a lack of formal recognition. The symbolism in the painting is moving, and the momentum of the woman as she plants footprints that must not be forgotten behind her while walking towards her recovery is inspiring. This painting offers solidarity and hope to other such victims, present as well as past.

Here is what the artist herself wrote about this piece: ‘My work is based on the theme of Japanese Military Sexual Slavery that occurred during the war between Korea and Japan. In Korea, rallies are held every Wednesday in front of the Japanese Embassy. This is to face Japan, who denies their atrocities and tries to make them look like they never happened. Victims had to spend countless days in pain after that, but now they are working as human rights activists who give comfort and hope to women victims of sexual assault around the world. The butterflies and flowers which are a symbol of the victims show that they are trying to overcome the painful memories and gain hope. They continue to fight back, keeping their place. I tried to express the victims of Japanese Military Sexual Slavery continuing to walk toward a bright future without giving in to despair, leaving clear footprints of their actions behind. Those footprints are the victims’ will to make Japan’s atrocities to be remembered in history, and a determination to move forward, not staying in the past. Their story is not over yet, and even at this moment they are writing a new chapter.’

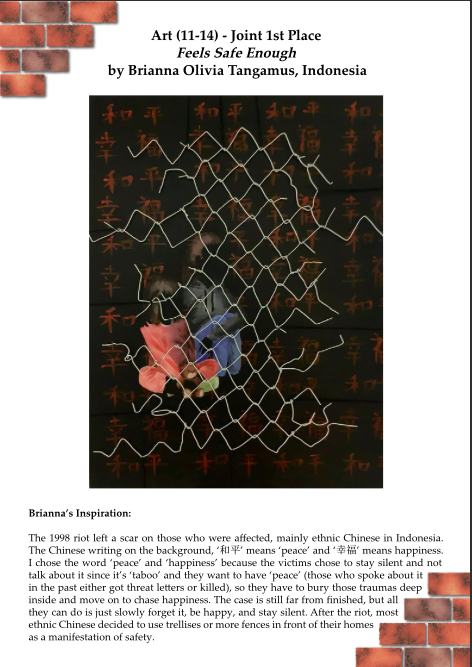

It was striking how many entries reflected on the individual, everyday things that victims of conflict have done or need to do for themselves to find peace in the aftermath of violence – rather than peace-building done by governments or international agencies. Like ‘An Unfinished Story’, Brianna Olivia Tangamus’ picture ‘Feels Safe Enough’ not only taught me about a past conflict that I am unfamiliar with; it also got me thinking about the very different ways in which victims of conflict try to seek security and heal from the scars of war. In particular, it draws attention the barriers (physical and metaphorical) which people sometimes erect to protect themselves after they have experienced conflict – barriers which can then become obstacles to truth, healing and reconciliation.

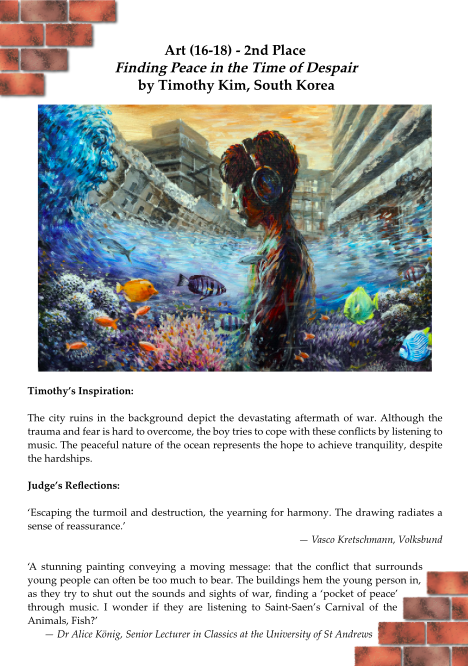

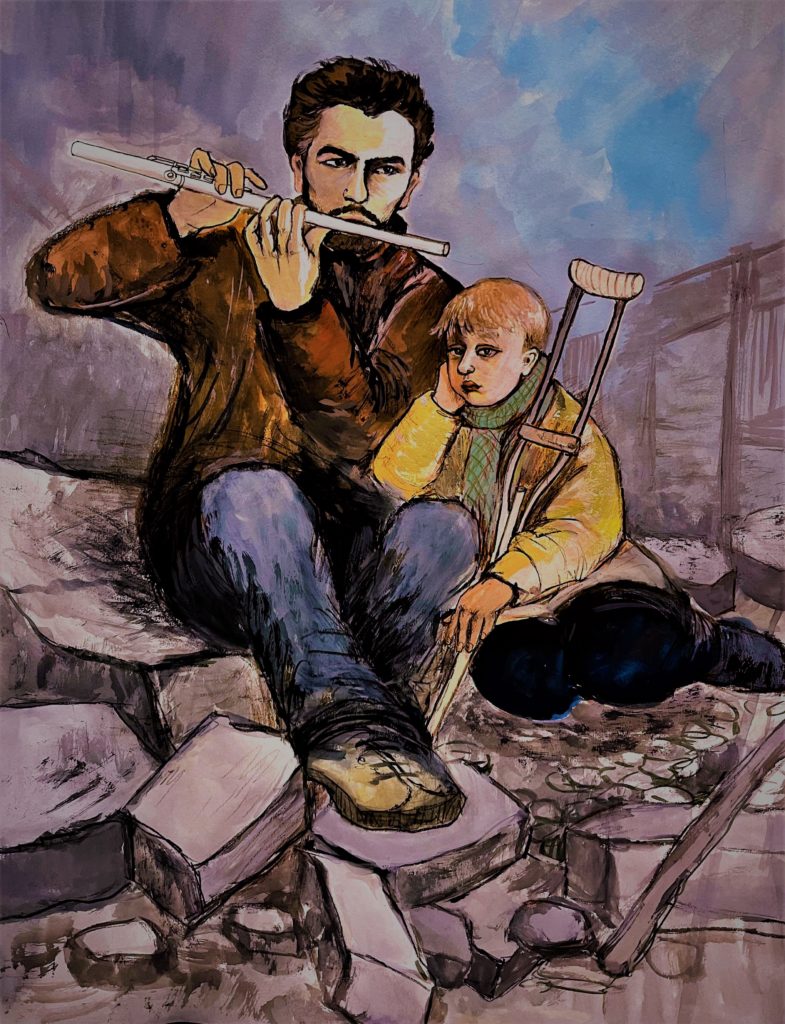

A number of entries reflected on the power of music to provide temporary sanctuary from conflict. On the left, Timothy Kim’s painting shows a young person finding solace from their oppressive surroundings by immersing themselves in their own soundworld. On the right, Yanjun’s painting shows a father playing his flute to comfort his child. Yanjun was inspired by scenes of people on social media, rescuing their instruments from the rubble of buildings in Ukraine, and he wrote this about his work:

‘In March 2022, many ordinary people’s homes were bombed in Ukraine. The father and son were sitting in front of their bombed-up home. The father played his beloved flute to comfort the injured child. The father was completely devoted to the music. Desperate encounters happen in an instant, but it takes a long time for people to accept the harsh truth. After the war, restoring normal life not only requires rebuilding homes, but also requires people to gradually come out of their sadness. This is a rebuilding of the mind and a huge project. A father’s music can’t make a child’s wound heal right away, but it can make the child stop worrying and crying. Music is a healing thing for anyone who is hurt. Despite the wars and conflicts, people did their best; showing human camaraderie in music. These flowing melodies can always help you express those unspeakable sorrows and arouse your yearning for love and beauty. This is how we live after conflict and respond to violence. Make music more lively, beautiful and engaging than ever.’

YANJUN, 11-14 – CHINA

As in Timothy’s artwork, impactful colour contrasts, stillness and the sombre but gentle mood of Yanjun’s painting all shine a spotlight on some key aspects of life (and self-care) after conflict: the emptiness, the loss of direction, the bewilderment, and the need to take stock. What lifts this from despair to hope is the centrality of the flute: as the son sits, head in hands, the father makes music, infusing the picture with a sense of agency and new life. Music can carry us beyond conflict.

Care for others was another recurring theme in how children’ visualised ‘life after conflict’. I particularly loved ‘Unnoticed Love’ and ‘Just a Warm Hug’. The first is an incredibly insightful work of art, exposing one of the many ripple effects of conflict: the brutalising impact of violence which can stifle overt expressions of love and care. And yet love and care persist, manifested in the small things – and they bring people together, slowly but surely. It is a powerful evocation of the way in which conflict damages interactions, of how slow recovery can be, but also of resilience and reconnection. In ‘Just a Warm Hug’, commemoration and care are the key themes. I was moved by the protective compassion in the hug of the young girl. It is a hug which cannot right past wrongs; but the warmth of that hug for past victims offers hope for the future. If we can all channel this kind of compassion and care, the world will be a better place.

Words from the artist (aged 14-16): ‘Though they were not able to have fancy foods due to financial difficulties, affordable foods such as kimchi and mixed grains brought warmth to the dinner table. The harsh conditions also made the mother’s care unrecognizable to the family since delivering love was not easy because of the hardships they experienced. Signs of love come in different scales; even small hand gestures that people do not notice immediately, such as pushing a bowl of rice towards the family, can be a big sign of love.’

Words from the artist (aged 16-18): ‘To remember the victims of the comfort women system during WWII, South Korea builds statues representing the victims. In the statue, the shortly chopped hair represents how the victims were cut off from their family and homes. The bird represents peace and freedom and serves as a mean of connection between us and the victims. In my drawing, the girl hugs the statue, wishing that the victims have found peace and promising that she will never forget.’

Children depicted many different forms of resilience. Two of my favourites were ‘Pray and Move Forward’ and ‘Hope’. The artistry in ‘Pray and Move Forward’ is breath-taking, and the focus on the hands resting in prayer or repose captures so much of the strength, endurance, suffering and resilience of the woman depicted and so many others like her. I was moved by the compassion of this young artist for older and historic victims of conflict. And I love the way that this painting tells a specific story at the same time as evoking a (tragically) more universal experience. The painting on the left is more intergenerational, and also more optimistic. The artist wrote: ‘After the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the siege of Sarajevo, life and hope were coming back to ruined country, healing the scars on human hearts and their homes. People could dream again and think about future, getting pieces of their lives together. In a ruined country, people just wanted to get back to their ordinary lives, enjoy in small things, in days without fear, death and terror. Children could finally get a chance to have a normal childhood, live and dream. We can’t undo our past, but we can create a better future.’ In this street scene, the rhythms of everyday life have begun to prevail over conflict. The Granny in the window reminds us of older generations and what they have been through. And the graffiti on the walls evokes the struggle and activism of ordinary people. There are echoes of past conflict; but the present is happy and relaxed. It offers hope that normality can return and children can get back to playing without fear. But we need to keep reading that graffiti – the messages remain important, even in times of peace.

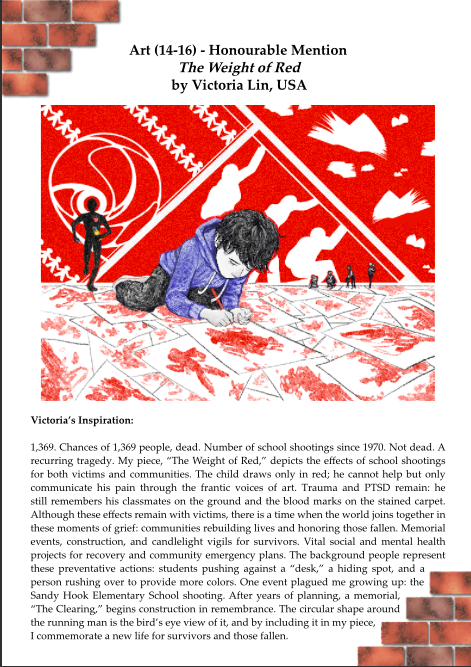

I want to end with two art entries that ground us not only in the 21st century but also in the lived reality of many children around the world. ‘The Weight of Red’ reminds us that children experience conflict outside what we might traditionally term ‘war’ – and also that, while supported by nurturing adults in the background, they have no choice but to develop coping mechanisms of their own. Life in the wake of this kind of conflict is marked by trauma that can only be partially mitigated by compassion and care. ‘It Takes Two to Clap’ offers some hope, however. As the artist explained, ‘In the modern and daily world of conflict, online gaming is one arena I encounter. Though its damage does not involve real shedding of blood, the psychological damage from hurtful language can be lasting. In my artwork, I wish to show how conflict can be managed and resolved in gaming, by being someone that shows grace to another participant, even if he or she is my gaming opponent.’ This painting gets us thinking about gaming as an activity that can militarise children’s mindsets but also how it could be turned into a solution, to help young people learn vital conflict-resolution skills. A wonderfully original idea with a real-world application, brought to life brilliantly through art.

These few examples are just a small selection of the artwork that was submitted to NSI’s competition in 2022 – and alongside the art were many poems, speeches and songs, all reflecting on life after conflict and what peace-building involves. What can we learn from them? Well, even amongst this small set, it is clear just how many different perspectives and interpretations children can offer, and also how well-informed so many of them are – with the ability to teach us adults about conflicts we have not heard of and impacts we have not thought much about. The understanding and empathy that children from different cultures, countries and continents express for each other is inspiring. One very great strength of NSI’s work is the way it forges not just intergenerational but also international dialogue; we need much more of this – and we need to involve children and young people – if we are to find more sustainable mechanisms for resolving and also preventing conflict.[2] Perhaps the biggest takeaway for me from these competition entries was that their young authors do not look at peace through rosy-tinted spectacles. While some propose or explore solutions (often focused around everyday acts of care and compassion, or grassroots forms of activism such as campaigning for post-conflict justice), they also drill down into the many different challenges that make recovery from conflict so difficult and time-consuming. They look hard facts in the face, put them under the microscope, critique past (adult) failings and are under no illusions about the magnitude of the task in any given situation to move beyond war to meaningful peace. That realism should be a great source of optimism for us – as is the tendency I saw in the artwork I sampled to see the human ahead of the politics, and to communicate with compassionate understanding. We should not idealise children any more than we should idealise peace; but NSI’s competition ‘Life After Conflict’ underlines the value of taking what young people have to say on war and peace seriously. Rather than thinking or talking about children as ‘the peacemakers of the future’, we should seize opportunities in the here-and-now to include and consult them.

What do you think?

- What did you learn from these representations of Life After Conflict?

- Did these young people change or stretch how you visualise peace?

- How can we make more opportunities for children and young people to contribute – and be taken seriously in conversations about conflict and peacebuilding?

- What are the benefits of listening to how young people visualise peace? What can we learn from them?

Please note: this museum entry relates to some wider research being conducted by the Visualising War project in collaboration with the charity Never Such Innocence, to develop new mechanisms for involving more children in conversations on conflict. You can read about our recent webinar featuring children’s voices on the war in Ukraine here.

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also like ‘Peace is Fun‘, ‘How to make a fruit basket for aliens‘, ‘Jojo Rabbit‘, ‘Pentagon Peace Pals‘ and ‘Unlearning War‘ and items with the tag ‘Marginalised Voices‘.

Alice König (April 2022)

[1] You can find some good examples of ‘artivism’ (activism via art) here and here. This podcast also explores the use of art to build peace in different parts of the world. One of my favourite pieces of ‘artivism’ in our museum is the work of graffiti artist Shamsia Hassani, who uses her art to comment on and campaign for women’s rights: https://peacemuseum.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2022/04/26/a-blank-newspaper/.

[2] You an read more about the Visualising War project’s work in this space here: https://arts.st-andrews.ac.uk/visualising-war/childrens-voices-on-war-and-peace/. This museum entry gives you a snapshot of some of the work we are beginning, with expert colleagues like Helen Berents and J. Marshall Beier, among others: https://peacemuseum.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2022/06/28/peace-is-fun/.