‘The city that was burnt

Was reborn on another coast’

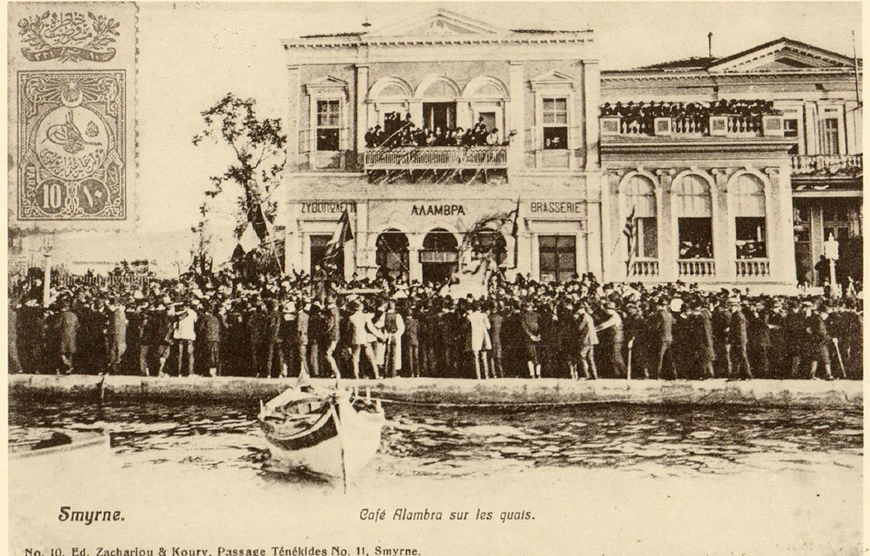

Despite popular belief that the First World War ended at 11am on the 11th of November in 1918, many areas across the world had to deal with the ramifications of this conflict years and even decades later. Greece may have emerged victorious from WWI, the Treaty of Serves giving it significant gains in Thrace and Smyrna, yet the Greco-Turkish war that broke out in 1919 and lasted until 1922 would undo much of that. The end to that conflict came with the burning and subsequent destruction of most of the port of Smyrna in September of 1922. The fire started on the 13th of September and lasted until the 22nd, resulting in the loss of between 10,000-125,000 Greeks and Armenians and the displacement of hundreds of thousands more. The poem, ‘The Ash that Travelled’, written during the 70-year anniversary of the fire, is interested both in the memories of the event as well as the struggles that came with the subsequent displacement of the people of Smyrna. K. Georgousopoulos, also known by his pen name K. H. Miris, is a second-generation refugee from Smyrna, as well as a literary and theatre critic, filmmaker, and teacher. I translated his poem from Modern Greek for inclusion in our museum.

Visualising Peace after Displacement

The first days, we holed up in our houses in panic.

Rolled down the shutters, latched the windows,

Sealed the cracks in the walls with rags,

Waxed the wrinkles on the wooden boards,

We stuck cross-shaped tape on the cracked windowpanes,

Turned the key twice and three times

In the keyhole.

In vain.

The rooms were filled with smoke and ash.

The city was burning right across.

In August nightmares travel all the swifter

With the Etesian wind.

Smoke and ash

Were drenching the walls,

Were sitting on the furniture,

Were smudging the mirrors,

They hung from the ceiling

And lived in the chinks.

Smoke and ash

Were crawling into the basement,

Were mingling with the wine

Giving it an acrid taste,

The flour got bitter

And the bread was muddy in our mouth.

Every now and then, our tongue

Could sleuth the ash

And in between our teeth

Were sprouting tiny specs of coal […]

The city that was burnt

Was reborn on another coast…

One with our body,

She flows in our blood.

And when we dream,

We saunter in her orchards

And cruise along her squares.

Every time we take up song,

Our words are ashy

And the music’s grievance,

Like the blaze carrying the Etesian wind.

The city of the East [1]

Resides within us

And sixty years now

She is judging us.

‘The Ash that Travelled’ by K.H. Miris, translation by Marios Diakourtis

As the title of K. H. Miris’ poem suggests, movement is a primary concern in this poem, and though the ash may be perceived as a signifier of destruction it can also be read as a remnant of conflict that must eventually settle down somewhere, much like the people who were forced out of their homes and into a new life across the sea.

The majority of the poem is concerned with the days of the fire and the vain attempts of the residents of Smyrna to deal with the invasive smoke and ash. The poem plays with the ideas of boundaries and home, as the ramifications of the fire entail an invasion of this private, secluded space. The home represents a haven from politics and the public sphere, or at least the persona wishes it were so; but smoke and ash eventually enter the home and the residents of Smyrna are forced to evacuate their properties.

As the poem goes on, the ash continues to cast a shadow, literal and metaphorical – ‘sixty years now’. Peace for the people of Smyrna did not come with the resolution of conflict, but with time and a reluctant acceptance of defeat, flight and loss. The glimmers of peace that they find are dreamlike (a calmer counterpoint to the nightmares near the start), and they revolve around their memories of the city they left behind: ‘when we dream, we saunter in her orchards and cruise along her squares’. Like a phoenix, Syrmna and its people are reborn from the travelling ash: ‘one with our body, she flows in our blood.’ The poet describes how his beloved Smyrna was rebuilt on another coast, probably a reference to an area in Athens named Nea Smynri (New Smyrna). As the poem closes, he introduces the idea that residents have a moral duty to their lost city, with Smyrna said to be judging them as they go about their new lives in continental Greece.[2] The lines of the metaphorical and the literal blur, as the physical reconstruction of the city in a different location is related to an almost dream-like recollection of spaces from the past that are emotional charged by nostalgia, identity, belonging and the idea of the home.

The fire at the port of Smyrna may have helped to end the Greco-Turkish war (itself a reminder that one conflict can often merge into another), but it sparked a new wave of loss and struggle for those affected. The speaker in the poem underlines that even decades later, true peace was not felt among the former Anatolians, as the bittersweetness in the heads and hearts of the refugees is the product of sorrow mingling with happy memories. The idea of singing confirms this, as melodising bitterness is on the one hand a way to cope with the pain, while on the other hand it is an accurate reflection of how positive and negative emotions can coexist in art. The poem itself attests to this, being at once an emotional conglomeration of lyrical lines as well as a painful reminder of loss. The poem constructs an intricate idea of peace, reflecting that for displaced people the absence of conflict does not bring a peaceful present. Rather, memories of a more peaceful past – elusive ‘pockets of peace’ – both stimulate and haunt survivors, as they try to create new lives in a new place which they fashion in the image of the old.

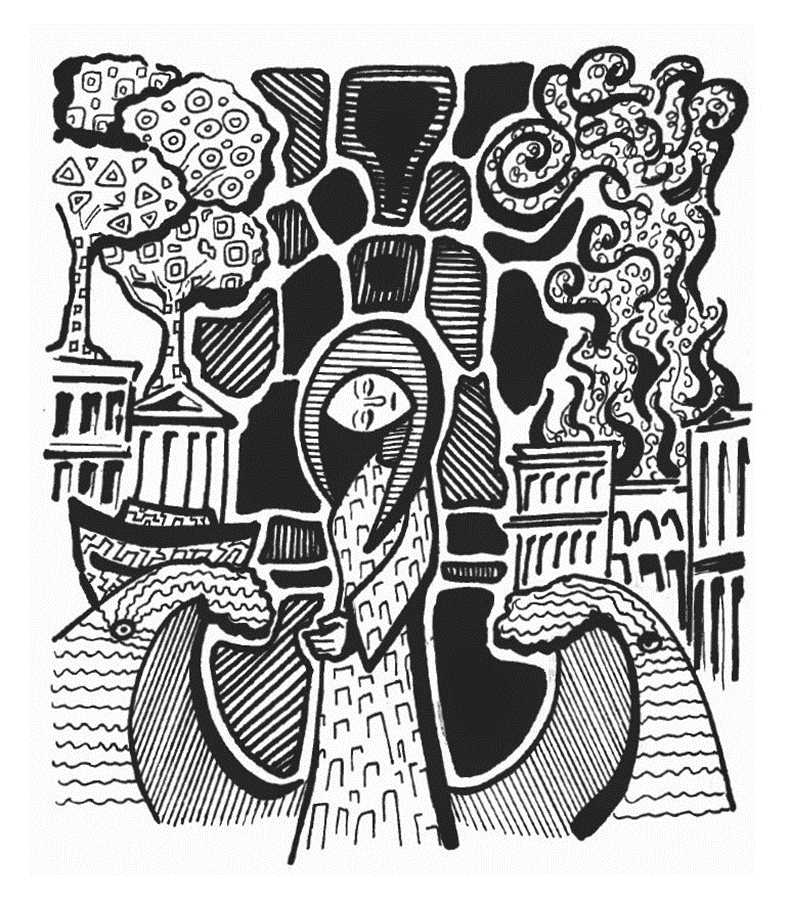

This emphasis on the ‘in-between’ experience of forced migrants is what inspired me to create the illustration accompanying the poem. It shows a woman standing between two ocean waves. On the right side, on top of one wave, stands a burning city with smoke billowing high, while on the left, there is a ship on top of the wave, and then another city from which trees appear to bloom. The female figure grapples between two cities and two situations, destruction and rebirth, conflict and peace. If you want to read more about my art, you might enjoy ‘Visualising Peace after Forced Displacement‘.

What Do You Think?

- Is accepting loss and moving to a different place (either literally or metaphorically) a necessary yet painful part of achieving peace after conflict?

- What role does the idea of home or a home country play in imagining peace?

- How might victims of displacement challenge or change traditional understandings of peace?

- What does this poem have to say about history being always written by the winners?

- What aspects of the poem does the artwork best capture?

- If you were illustrating the vision of peace conveyed in this poem, what would you draw?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also like ‘Jasmine‘, ‘Lament for Syria‘, ‘Visualising Peace after Forced Displacement‘, ‘Of Ordinary Things‘, and other items with the tag ‘Refugees‘.

Marios Diakourtis, April 2022

[1] In the original, the word used, Ανατολή (=Anatoli), can mean the East, dawn, as well as be a reference to the location of Smyrna in Asia Minor, also known as Anatolia.

[2] While translating this poem from Greek to English, there were a few words whose essence I found particularly hard to capture in a different language, one such word being the final verb, ‘judging’ (=δικάζει). Like the English version of the verb, ideas of being perceived and trialled remain consistent, yet the Greek verb does a better job in connecting judgement with justice (=δικαιοσύνη/δίκαιο), which I believe was the intention of the poet.