Trigger warning – discussion of the Holocaust

“We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful what we pretend to be.”

“If I’d been born in Germany, I suppose I would have been a Nazi, bopping Jews and gypsies and Poles around, leaving boots sticking out of snow banks, warming myself with my secretly virtuous insides. So it goes.”

Kurt Vonnegut’s Mother Night was written in 1962, a year after Adolph Eichmann’s trial in Israel. It takes the form of a memoir written by Howard J. Campbell, a fictional German-American playwright and writer who became famous for writing pro-Nazi propaganda during World War II. However, early in his account, Campbell claims he was an American spy during the war, passing on coded messages during radio broadcasts attempting to convert Americans to the Nazi cause. The information Campbell passes on to the CIA, communicated through pauses and coughs during his radio broadcasts, is unclear, either because Campbell was never told the information he communicated or because his alleged spying was a lie.

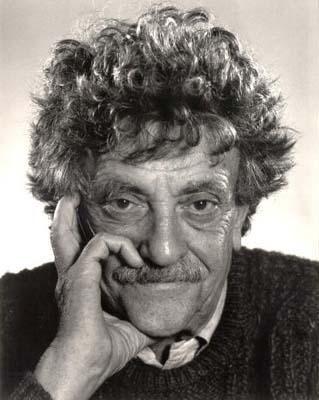

Author Kurt Vonnegut was of German descent, and both his parents spoke German fluently. He fought for the US during World War II and was a prisoner of war during the American bombing of Dresden, which became the inspiration for one of his most famous novels, Slaughterhouse-Five. Throughout his career and life, he was critical of the American government and the West more generally, becoming a vocal opponent of the Vietnam and Iraq Wars. He was also known for his satire and dark sense of humour, which is occasionally difficult to distinguish from his more serious, straightforward prose.

Mother Night is famously an example of metafiction, or a story-within-a-story intended to make the audience hyperaware that what they are reading is fiction.[1] The novel is written as the memoir of a Nazi, but all the way through we are invited to question whether Campbell tells us the whole truth, or if his account of his life, crimes, and capture is biased, misleading, or downright fictional. This helps the novel reflect critically on some key aspects of conflict resolution: both the character’s complex process of reconciling himself with his actions and identity after the war, and the wider legal processes that were set up after WWII to determine blame and dispense justice.

Particularly toward the end of the novel, Vonnegut interrogates the question of culpability as his protagonist oscillates between escaping from justice for his involvement in Nazi propaganda (helped by US agents, who play a murky role throughout the novel) and taking responsibility for his ‘war crimes’, however well-meaning he may (or may not) have been when he committed them. Complicity and culpability become very hard to pin down, both at the moral and the legal level; and the novel casts some doubt on the post-war legal processes because they are so easily evaded or manipulated by Campbell’s American ‘handler’. There are lots of blurred lines in the novel, both during the war and afterwards. Campbell straddles a blurred boundary between civilian, American spy and Nazi supporter; and post-war, he oscillates between victim and perpetrator, innocent and guilty.

At the beginning of the novel, Vonnegut himself tells us that, had he been a German citizen during World War II, he would likely have gone to war for Germany just as willingly as he fought for America, participating in the same war crimes that his fictional protagonist sanctioned and encouraged. The implicit question underlying this statement is whether we the readers would do the same, aligning ourselves with oppressive governments and ultimately committing crimes on their behalf, while ‘warming ourselves with our secretly virtuous insides’, as Vonnegut puts it. In other words, we are invited to wonder what fictional stories we might have told (or might tell) ourselves to ‘make peace’ with our own ‘well-meaning’ contributions to conflict – or whether we would (or could) walk a different path. Would we resist, refuse to engage, remain non-compliant (and so stand up to conflict and fight for justice and peace) or would we opt for the more ‘peaceful’ life of gradual compliance, which leads to complicity and culpability?

I chose to include this novel in my list of peace narratives not because it offers a particularly clear vision of peace itself, but because it presents the opposite: a world in which there is surface-level peace, but the underlying tensions and acts of violence committed during the then 20-year-old war remain. Vonnegut himself admits he does not provide solutions in his novels, joking in his book If This Isn’t Nice, What Is? that when his children ask for his advice, he tells them, ‘Shut up, I just got here myself.'[2] Mother Night is not so much a book presenting a solution for the future so much as offering a meagre coping mechanism: Campbell must answer to himself for his crimes, and whatever we have done or might do, we must also be prepared to do the same.

What do you think?

- Who bears guilt in a war? Is there such thing as an innocent bystander? What kinds of involvement are culpable, and who decides?

- What does compliance and culpability in conflict do to our inner peace?

- How do post-conflict legal systems determine guilt and dispense justice?

- And what contribution do they make to peace-building? How exactly does the pursuit of post-conflict justice intersection with the establishment of (a sense of) peace?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy ‘JoJo Rabbit‘, ‘Achilles in Vietnam‘, ‘Story #1913‘ and items with the tag ‘Elusive Peace‘.

Arden Henley, May 2022

[1] Hume, Kathryn. “Vonnegut’s Self-Projections: Symbolic Characters and Symbolic Fiction.” The Journal of Narrative Technique 12, no. 3 (1982): 177–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30225939.

[2] Vonnegut, Kurt. If This Isn’t Nice, What Is? (Much) Expanded Second Edition: The Graduation Speeches and Other Words to Live By (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2020).