‘Oh Syria, my love

You can hear Amineh Abou Kerech reading the full poem here.

I hear your moaning

in the cries of the doves’

As of the 15th of March 2022, the conflict in Syria completed its eleventh year. Starting as a pro-democratic peaceful protest in 2011, what has developed into the Syrian civil war has claimed over half a million lives according to current estimates, and the death toll goes up daily. However, the situation in Syria is more than a civil war, with many other countries feeling its ongoing ramifications. Some nations actively participate in the dispute; Russia and Iran in support of the Syrian government, while Turkey, the West, and other Gulf States have intervened in support of the opposition. Meanwhile, many other countries across the Middle East, the Mediterranean and Europe have faced and are still facing one of the largest refugee crises of recent history. Of the pre-war population of Syria (22 million), over half of these people have been displaced, either internally or externally.

Amineh Abou Kerech is one of these people, forced as a teenager to transition from childhood to adulthood while also moving from peace to conflict to refugeehood. She fled her homeland in 2012 for Egypt, before eventually moving into the United Kingdom. Her poem ‘Lament for Syria‘, written when she was just 13 years old, won the Betjeman Poetry Prize in 2017 for its poignant and insightful perspective on the Syrian conflict.

‘Lament for Syria’ by Amineh Abou Kerech

Syrian doves croon above my head

their call cries in my eyes.

I’m trying to design a country

that will go with my poetry

and not get in the way when I’m thinking,

where soldiers don’t walk over my face.

I’m trying to design a country

which will be worthy of me if I’m ever a poet

and make allowances if I burst into tears.

I’m trying to design a City

of Love, Peace, Concord and Virtue,

free of mess, war, wreckage and misery.

Oh Syria, my love

I hear your moaning

in the cries of the doves.

I hear your screaming cry.

I left your land and merciful soil

And your fragrance of jasmine

My wing is broken like your wing.

I am from Syria

From a land where people pick up a discarded piece of bread

So that it does not get trampled on

From a place where a mother teaches her son not to step on an ant at the end of the day.

From a place where a teenager hides his cigarette from his old brother out of respect.

From a place where old ladies would water jasmine trees at dawn.

From the neighbours’ coffee in the morning

From: after you, aunt; as you wish, uncle; with pleasure, sister…

From a place which endured, which waited, which is still waiting for relief.

Syria.

I will not write poetry for anyone else.

Can anyone teach me

how to make a homeland?

Heartfelt thanks if you can,

heartiest thanks,

from the house-sparrows,

the apple-trees of Syria,

and yours very sincerely.

Written while Kerech was still trying to grapple with the realities of leaving behind a home country torn apart by war, this poem is a poignant reanimation of Syrian values imagined through the memory of a thirteen-year-old girl. Kerech understands that her country is currently at war, yet she longs for peace and dreams that through her poetry she might be able to help heal Syria. As well as trying to visualise or engender peace for her country, her final stanza also hints that she is trying to find some kind of inner peace in the place she now lives. She wants a peaceful ‘homeland’, both for Syria and herself.

The vision of the doves, a traditional symbol for peace is here ambiguously employed by the poet, as their crooning is what launches a poem that will tell a story of war while advocating for a solution towards peace. The fact that the doves are Syrian and are at the time of the poem above the persona’s head suggest that either she is still back in Syria, or that the doves, or at least the idea of them, have travelled with her across borders. This idea of reinventing something familiar is common in stories by refugees, as it follows the trope of getting the person out of the place, but not the place out of the person.

For Kerech, the cries of the doves are conflated with the cries and moans of her personified county as ideas of peace and conflict are coalesced, ultimately creating a sensory cacophony that is meant to invoke a sense of urgency to the reader. But that is not all. Kerech is not only interested in presenting a current image of Syria that is ravaged by bombs and death. Instead, she turns to pockets of peace from the past, sharing some well-cherished instances from her memory that are representative of the virtues of Syria, even as the world cannot see them because of the war. Ideas of respect, family, community, and the reverence towards bread as a symbol of sustenance, are but a few reminders of what a peaceful Syria looks like, and the fragrances of coffee and jasmine help in bringing those to life.

An implicit question in her poem is whether or not these pockets of past peace can be revived. Her poem also invites us to ask: can poetry itself bring peace? Despite the sights and sounds of war, her verses conjure a vision of a country and culture that has great potential for peace in the future, not just a peaceful history. This vision perhaps brings the author (and reader) some respite and inner peace; but the poem is also about home-(re)making and city-(re)building, and poetry itself seems bound up with that endeavour. On the one hand, it represents the lone lament of a refugee girl whose country has been trampled by soldiers; on the other, it shows us that Syria’s spirit can be reanimated and peaceful times can be revived by the power of the pen.

The poem closes with Kerech addressing the reader, the global community, or basically anyone who cares to listen, as she asks for help in imagining a new ‘homeland’ that is pretty much like the old Syria, a peaceful place where people are not afraid to live and a place Kerech may one day be able to return to. Her appeal for help combines past and present, Syria and not-Syria: she ends the poem in a liminal place, hovering between old and new, war and peace.

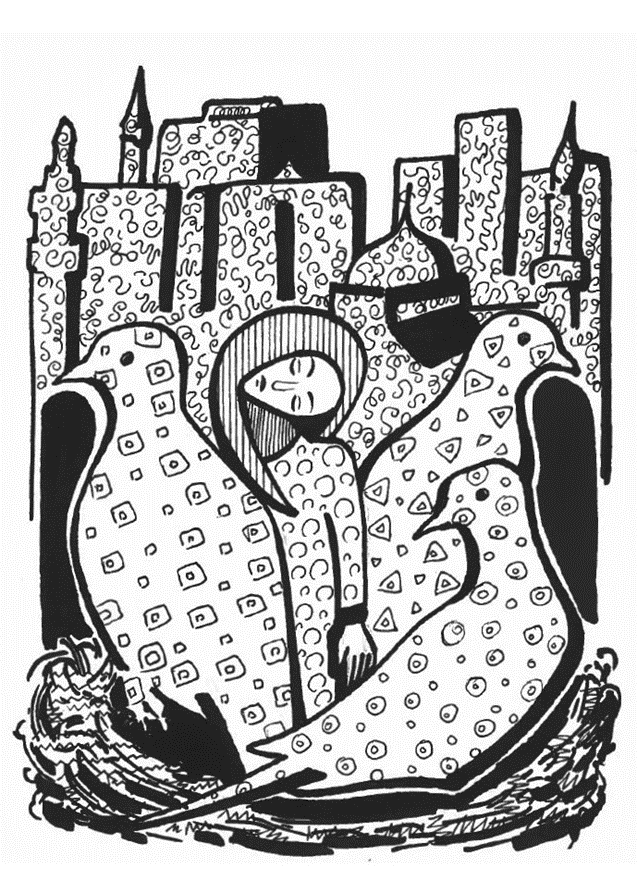

I have tried to capture that idea of liminality in the illustration I drew to accompany the poem. The dove’s nest highlights the idea of home and belonging, which the skyline of Damascus in the background helps to pinpoint geographically. The depicted figure is thus positioned between the crooning doves and the memory of Syria in her search for peace, as she is forced to ‘build her nest’ elsewhere.

What do you think?

- How do peace and conflict sit alongside each other in Kerech’s poem? And what does this teach us about peace?

- How connected are peace and a sense of home or home-making?

- What role does the past play in visualising a more peaceful future – in Kerech’s poem and more generally?

- How do the experiences that Kerech illustrates in her poem correspond to the more generalised picture painted by the press about what forced migrants experience?

- In what ways might the voices and experiences of forced migrants change how we think about post-conflict recovery, peace-building and peace itself?

- If you were ‘trying to design a city of Love, Peace, Concord and Virtue, free of mess, war, wreckage and misery’, what would it be like? If you want to read more about my art, you might enjoy ‘Visualising Peace after Forced Displacement‘.

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy ‘The Ash that Travelled‘, ‘Jasmine‘, ‘Of Ordinary Things‘, ‘Pockets of Peace in Ukraine: care for animals‘ and items with the tag ‘Marginalised Voices‘.

Marios Diakourtis, April 2022