These children will need to learn something as basic as how to play normally, peacefully, to get beyond acting out the dreadful violence to which they were exposed, to go to school as a regular, normal thing. There are children who need to unlearn war and violence and extremism… Every child who arrives for school clutching a breakfast pastry and an exercise book, every face turned towards the teacher in class time, every hand up to answer a question means hope and some healing. Along with their lessons, they are learning how to be children again, and to rediscover joy. But each time a controlled explosion happens, because yet another mine has been discovered in the rubble, or they hear a sudden sharp or shouted word, men arguing, or they see gangs in the playground that get carried away, or sometimes for no obvious reason at all, the children still flinch and cower. Then the work of rebuilding begins again, brick by brick, lesson by lesson, child by child – the real infrastructure of the city.

Emily Mayhew, The Four Horseman and the Hope of a New Age, 2021: pp. 72-73

(photo by Peter Biro, European Union)

In 2014, the Iraqi city of Mosul was captured by ISIS. As historian Dr Omar Mohammed recounted via Mosul Eye – the blog he wrote to document what was happening – there followed two years of brutal conflict and oppression, as ISIS imposed harsh new rules on women and persecuted religious and ethnic minorities.[i] Attempts by Iraqi forces to recapture the city culminated in the long-drawn-out Battle of Mosul (2016-17), when ISIS was finally driven out.[ii] The violence surrounding Mosul’s liberation was as terrible as that perpetrated during its occupation – violence that left terrible psychological as well as physical scars.[iii] As Dr Mohammed wrote on 6th November 2016:

‘Two years of training on savagery and brutality, and I am scared to death of what might unfold during the liberation. People who act with such cruelty and barbarity open the door to upcoming and deep problems in the future. There are hundreds of thousands of children who might have turned into future monsters.’

Another historian, Dr Emily Mayhew, has been studying the impacts of Mosul’s occupation and liberation on children as part of her wider work on the wounds of war and the history of humanitarianism. In her book The Four Horsemen and the Hope of a New Age, she draws on the Mosul Eye blog to chart both suffering and recovery in Mosul. Part of the team that put together the Paediatric Blast Injury Field Manual, she has looked at how children live long-term after losing limbs in explosions. She is also interested in the effects of less visible injuries, such as the lasting impacts of famine on children’s physical and neurological development.

Her work connects closely with the research done by Save the Children into children’s ongoing mental distress years after Mosul’s liberation.[iv] Their research has drawn attention to the challenges of getting children back into school:[v]

To add to the strain, many children are struggling to return to school because half of all schools in conflict-affected areas have been destroyed. Nearly one third of adolescents reported never feeling safe at school and only a quarter said they thought it was a safe space… Twelve-year-old Fahad* from West Mosul now attends a school with damaged walls and no doors. “I don’t feel good in the class,” he said. “In this area, the sniper targeted the children so that when the mothers and fathers came to rescue them, he would shoot the whole family. The school got badly hit and the area became a frontline. The whole street became a frontline.”

https://www.savethechildren.org.uk/news/media-centre/press-releases/mosul-s-children-haunted-by-constant-fear-and-intense-sorrow-a-y

And yet education is vital not only to each child’s recovery but to a peaceful future for everyone, in Mosul and beyond. As Dr Mayhew writes: ‘The E in UNESCO is for Education. At the heart of the Revive project is the highest-stakes restoration of all: significant investments in access to quality education for the children of Mosul.’[vi] The challenges are huge: ‘there still aren’t enough desks and chairs, let alone child psychologists’; ‘most children from the city have missed years of education’; ‘it’s a different kind of catch-up for those who were malnourished, who have growing to do so they can walk to school, and participate in games, and follow the lessons to get back up to the grades they should be getting, so their families can plan for the future’; ‘children come to school having wet their bed, or exhausted by too little sleep full of “bad dreams that everything in Mosul is destroyed”…’.[vii] People persevere, however, because they know that ‘reviving the spirit of Mosul’ ultimately relies on helping children learn to play again, and helping them learn to study again, step by step.

From Nelson Mandela to Malala Yousafzai, campaigners and activists all around the world have connected education to peace-building. I wanted to include Mayhew’s analysis of the slow but important process of getting children back into schools in Mosul in our museum because I think it can help us visualise peace and peace-building in a number of important ways.

It reminds us how much work is involved, how stop-start the process can be, and how many set-backs people face along the way. Peace-finding and peace-building are not linear processes, perhaps for children most of all. For every step forward a child may take, there can be two steps back. And yet failure is not an option, because going backwards means getting sucked into a cycle of more trauma and more conflict. As Mayhew puts it, ‘each time a controlled explosion happens, because yet another mine has been discovered in the rubble, or they hear a sudden sharp or shouted word, men arguing, or they see gangs in the playground that get carried away, or sometimes for no obvious reason at all, the children still flinch and cower. Then the work of rebuilding begins again, brick by brick, lesson by lesson, child by child…’.

Mayhew draws a direct connection between children’s inner peace and wider peace-building efforts, with the physical space of the school, the input of teachers and education itself creating vital bridges between the two. Bridges that work in both directions. When schools feel safe, children feel safer; and then the work of saving the world from future conflict can really begin, as children begin to ‘unlearn war’ and have the chance both to learn about and to live that elusive phenomenon: peace.

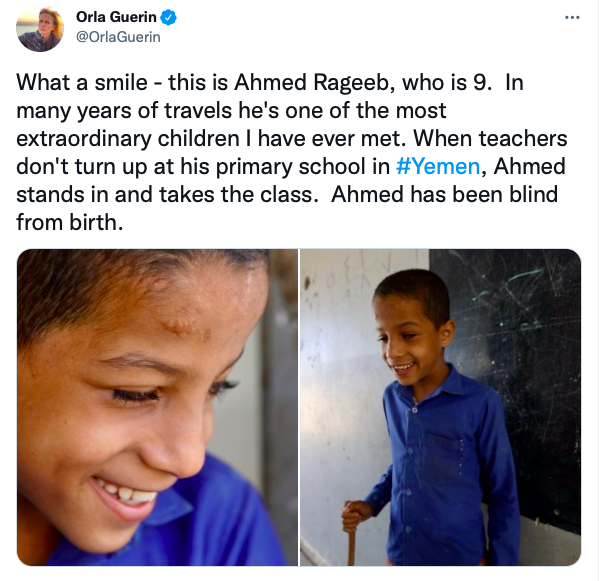

This may only happen for a few hours a day. The switch that Mayhew makes from children arriving with their breakfast pastries to the sounds of conflict reminds us that for many living through or in the aftermath of conflict, small ‘pockets of peace’ are all that they can hope for. This is certainly the case for Ahmed and his classmates in Yemen, whose front-line school functions whenever it can in the ruins of a bombed-out building: a small, fragile pocket of ‘everyday peace’ in a war zone, providing children with a fleeting sense of normality and progress, against the odds. And yet, as Dr Frank Möller stresses in his work on visualizing peace through photography, if we can string enough pockets of peace together, they can become vital stepping-stones in building more sustainable pathways to peace. There is great hope in the progress that a single child can make, in a single lesson, on a single day, especially if we can join up more and more lessons and more and more children over time.

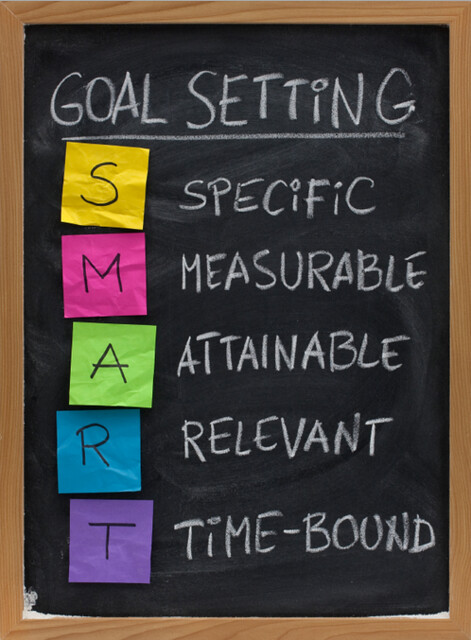

Perhaps the thing I like most about Mayhew’s analysis is that is helps us visualise peace-building as a process that involves setting SMART goals. The peace-building we read about in Mayhew’s book is bottom-up, not top-down. It involves a wide array of people – pharmacists, historians, vaccinators, engineers, doctors, and teachers – all playing their part to stand in line against war and nurture post-conflict recovery and peace-building from the grassroots. Rather than visualising peace as a far-off ideal, or something crafted for the wider public by powerful ‘peace architects’ sitting around negotiating tables in government buildings, she helps us grasp the ‘specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely’ steps which individuals – we – can take to build it, brick by brick, lesson by lesson, child by child.

What do you think?

- How useful do you think ‘SMART goals’ are when thinking about peace-building?

- How optimistic or pessimistic do Mayhew’s reflections on the restoration of education and childhood in Mosul make you feel?

- How important a role do you think education plays in post-conflict recovery and peace-building?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy ‘Hope in a Jar’, ‘Green Mosul’, ‘Of Ordinary Things‘, ‘Education: a force for sustainable peace‘, ‘Peace is Fun!‘ and other items with the tag ‘Children‘.

Alice König, April 2022

[i] Christians and Yazidis were particularly persecuted: see, e.g. https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/190620141 and http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/isis-hundreds-yazidi-captives-slaughtered-mosul-1499459.

[ii] Omar Mohammed discusses his experiences in this podcast: https://www.buzzsprout.com/1717787/9181282. You can hear a fuller account here: https://extremism.gwu.edu/mosul-and-the-islamic-state.

[iii] This harrowing article offers a glimpse: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/nov/21/after-the-liberation-of-mosul-an-orgy-of-killing.

[iv] You can read the full report here: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Picking%20Up%20the%20Pieces%20online%20version%5B1%5D.pdf. Key findings include: ‘almost half of children surveyed felt grief all or a lot of the time’ and ‘fewer than one in 10 children could think of something happy in their lives’. This blog by UNICEF offers further insights: https://blogs.unicef.org/blog/responding-iraq-learning-crisis/.

[v] The data in this article can help us visualise the challenges that families faced during ISIS’ occupation of Mosul, with some stats on school attendance: https://conflictandhealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13031-018-0167-8.

[vi] Mayhew, The Four Horsemen and the Hope of a New Age, 2021: p. 70.

[vii] Mayhew, The Four Horsemen and th.e Hope of a New Age, 2021: p. 71-2. Mayhew’s analysis was inspired in part by this Mosul Eye report.