After two failed attempts to have UN peacekeepers assisting civilians in Israel and Palestine, The Heads of Churches in Jerusalem, an ecumenical forum representing all major Christian traditions, called on the World Council of Churches (WCC). They asked the WCC to form an international presence, advocating for a just peace; in response, the WCC formed the Ecumenical Accompaniment Programme in Palestine and Israel (EAPPI). EAPPI is an international coalition that sends around 25 Ecumenical Accompaniers (EAs) to Palestine and Israel for three-month periods. They are supported by permanent teams in Jerusalem and Geneva and a Local Reference Group of stakeholders. Around 1800 former EAs commit to public engagement within their home country, giving talks and participating in panels on the conflict. Although it is run by the World Council of Churches, being an EA is open to all faiths and none and does not engage in proselytising.

EAPPI operates under a model called accompaniment. Accompaniment involves many key principles, three of which are: monitoring human rights violations, a protective presence, and nonviolence. Other organisations that use the model of accompaniment in Palestine and Israel (though with slightly different emphases) include the more activist International Solidarity Movement, locally run Rabbis for Human Rights and, before 2019, The Temporary International Presence in Hebron. Further afield, Peace Brigades International and Community (formerly Christian) Peacemaker Teams operate worldwide. Jessy Hampton describes the wide-ranging activities entailed by accompaniment:

‘Accompaniment, like its cousin “solidarity,” is multifaceted, complex, and involves difficult conversations about privilege and justice; it can be a literal, embodied “walking with,” like escorting Palestinian kindergarteners to school past military checkpoints and Israeli settlements, or slightly more abstract (though no less meaningful), like commitments to partner with and support the work of justice-seekers.’

Jessy Hampton (2016) “Accompaniment in Palestine,” Quaker Religious Thought: Vol. 127, Article 6, p. 50. Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt/vol127/iss1/6

EAPPI, with its Christian roots, particularly stresses the theology of accompaniment. In fact, during the founding of EAPPI, the WCC called for ‘churches worldwide to accompany the churches of Jerusalem and their communities with prayers, statements, advocacy and actual presence.’ Their form of accompaniment is explicitly Bible-based, aiming to replicate Jesus’ model of seeking justice. EAPPI also strongly emphasises former EAs’ advocacy and public statements as forming part of the wider accompaniment method.

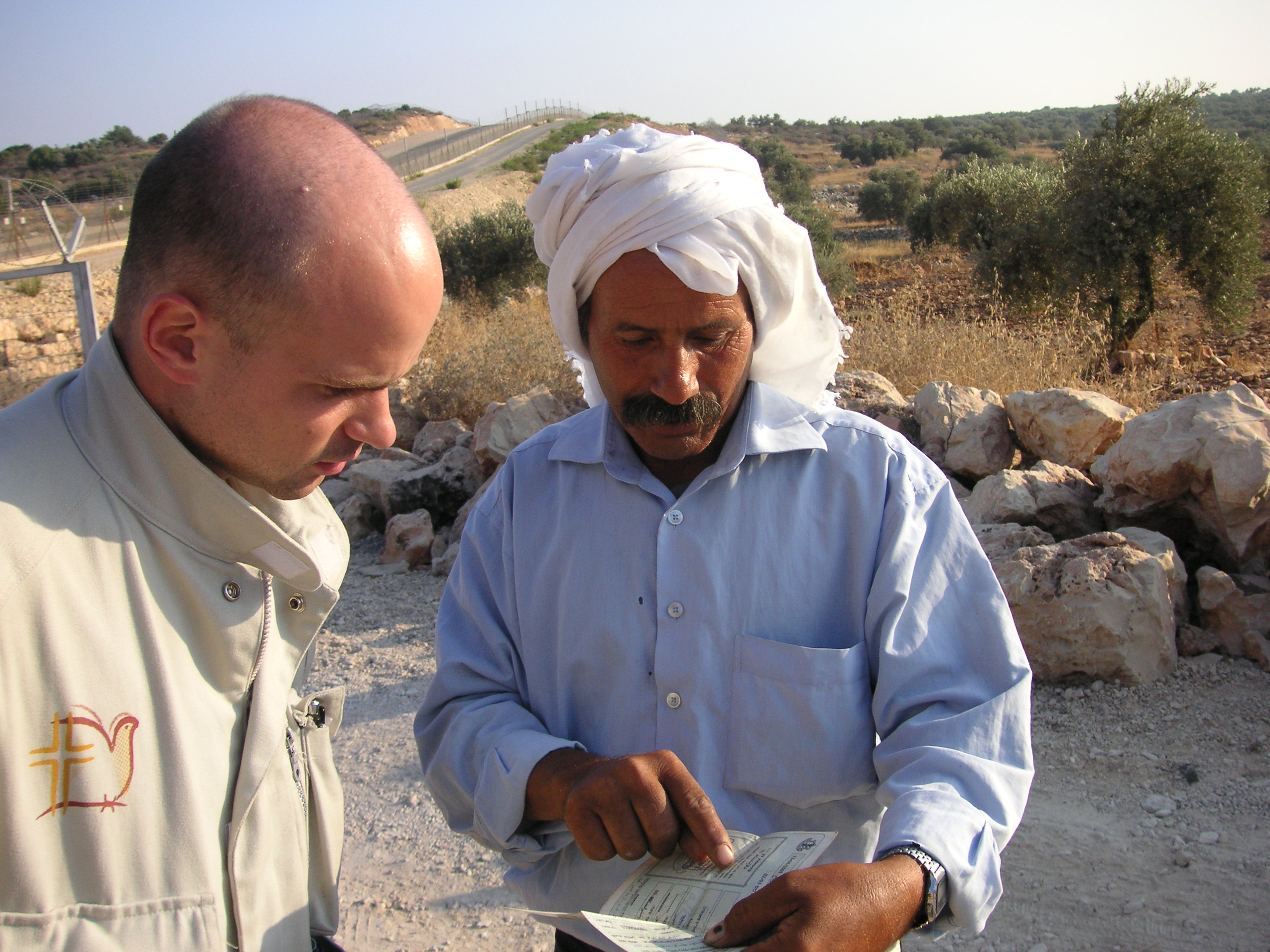

The bulk of activity that EAs carry out is the monitoring of human rights violations. These act to provide a protective presence, where those at risk are more able to go about their daily lives and where perpetrators also realise the cost of abuses and (ideally) change their actions accordingly. In a sociological example of the observer effect, the act of observation itself can determine the physical reality of whether someone may pass through a checkpoint or not. Through monitoring, EAPPI is able to report violations to the UN, human rights NGOs and the wider public, with the hope of increasing public pressure on the perpetrators. For this, nonviolence is crucial, both in their own actions and in only associating with other non-violent organisations. This is justified pragmatically as well as ethically: when they are not perceived as a physical threat, they have mostly unimpeded access on the ground to all sides.

This observational framework has become contentious when done in the context of Palestine and Israel, though. EAPPI is regarded by some as one-sided, antisemitic and uninvited. EAPPI has also been perceived as Western pandering, ineffective, or premised upon (and not challenging) state racism. The root of many of these complaints is the apparent passivity of observation; without actively intervening, it is easy to misunderstand their actions as not realising (or indeed changing) the gravity of the situation. Jessy Hampton argues that accompaniment should be more explicitly related to allyship: EAs should do more to challenge their own privileged position as (mostly white) international observers – locals observing human rights violations should be enough. Others accuse EAPPI of a hyperfixation on Israel’s wrongs, rather than Hamas’ violence or Saudi autocracy.

One response to these very different criticisms is similar: their engagement in the conflict is conditional upon an invitation from local churches, civil society and peace organisations. The model of accompaniment only works with heavy local participation. Even though it is imperfect, eight in ten Palestinians polled felt EAPPI’s presence at checkpoints was important, with over seven in ten believing that when an EA was there they crossed more quickly and with fewer incidents of harassment. Even larger majorities say they feel safer, more empowered, and more confident crossing when an EA is present. EAPPI’s work displays impressive levels of engagement, local involvement and impact; their accompaniment model is an extremely valuable toolbox, which more human rights, peace-making and peace-keeping organisations could follow. Observation does not make huge strides in peace-keeping or peace-building, but it makes many small and productive steps. Accompaniment illuminates the gradual and slow nature of peace-building, providing food for thought about what proper allyship looks like.

What do you think?

- How useful is the model of accompaniment as a peace-keeping or peace-building method?

- Does monitoring human rights violations actually change perpetrators behaviour?

- How important is local engagement for international peace processes?

- How neutral or partisan does the EAPPI programme seem to you?

- What is the role of religion in peacekeeping?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You might also enjoy The Place of Principled Impartiality in Peace Work, The Place of Neutrality in Peace Work, Peace in Faith and Practice, Pride: peace in social justice and the power of solidarity and this podcast on EAPPI’s work: Principled Impartiality and Accompaniment in Peacebuilding.

Robert Rayner, November 2023