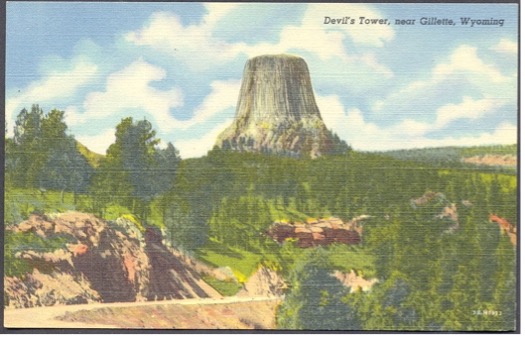

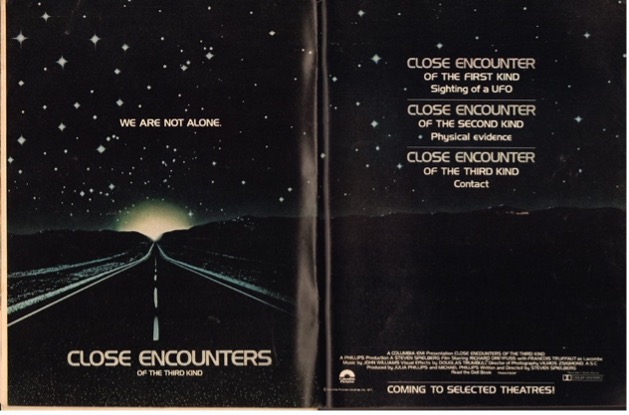

Close Encounters of the Third Kind is a 1977 film written and directed by Steven Spielberg, detailing a “first contact” scenario culminating in the American desert. The film follows three narratives: that of a woman and her young son who have established contact with extraterrestrials, of a man plagued by visions of the contact event, and of the government agents working to understand the codes sent to them by the aliens. These three narratives meet as all three groups decode the messages sent to them and travel to the Wyoming desert to contact the aliens.

The fundamental question posed by “first contact” films (that is, films which detail humanity’s first encounters with extraterrestrial life) is that of language: How would you go about communicating with a new species? What language should you use? Should you use language at all? Would images be more useful? Different films provide different solutions to this: in Carl Sagan’s Contact, aliens communicate with top astrophysicists using mathematics and binary, while the image of a white dove is interpreted as a hostile symbol in Independence Day, an idea comedically mirrored in Mars Attacks!. These films highlight language’s potential to fail as a peacebuilding tool, an idea reflected in real life instances of mediation and post-conflict negotiation. Close Encounters offers an alternative: one where communication is established through physical and metaphorical connection rather than language. Rather than attempting to communicate a particular phrase or intention, Spielberg’s aliens broadcast music, which translate to a series of numbers corresponding to geographical coordinates. When the two species meet at the location specified, they connect by playing music back and forth, often collaborating to create new sounds and songs. The characters in Close Encounters establish contact and mutual good intentions by coming into harmonious dialogue and creating art together.

Music, and art more generally, are a uniting force throughout the film and in real life. Art has a universal, connective power that few other mediums possess, in part because it is non-verbal. It brings people together, whether that’s in an art gallery, or a late-night jam session with an alien species. While art and music can themselves be coded in ways that reflect and speak to the cultures they come from, they do not necessarily rely on culturally specific language or allusions to make meaning. In many cases, the act of making art (not war) is enough to signify peace or at least non-violence. After all, it’s difficult to make a fundamentally generative act like making art into a reductive or destructive one. The film is aware of this concept and uses these ideas to its advantage. In a metatextual commentary on the universality of art, renowned French film director Francois Truffaut plays the UN’s interpreter for first contact. In watching an artist whose films most Americans are not familiar with decipher and translate music and language, we see the power that cross-cultural connection and art have in peacebuilding. Communication is not the key to peacebuilding; rather, connection is, and art connects people regardless of whether they speak French, whether they can read music, and whether they even belong to the same species.

The emphasis on connection also allows us to view events in the film that could be considered aggressive acts in a different, more peaceful light. Close Encounters begins with a dozen planes which had gone missing during World War II being returned to Earth. Their pilots are returned as well at the end of the film. In science fiction, alien abduction is generally considered to be aggressive, resulting in violence done to individuals and in some cases leading to species warfare. Over the course of this film, we learn that alien abduction is merely a way of understanding the human race before attempting to make contact. Connection on a broad scale, facilitated by small-scale connection and a willingness to learn and create alongside one another, allows us to re-imagine aggressive acts as overtly peaceful ones. Just as this idea makes first contact with an alien species more peaceful, so too can it make relations between hostile groups more peaceful and connective rather than destructive and violent.

What do you think?

- Do you agree with the argument that peaceful interactions depend more on connection than communication?

- How else can we connect without using language?

- What is the value of connection, not just after conflict but in everyday life?

- What examples have you come across of art facilitating peace-making in the wake of conflict?

If you enjoyed this item in our museum…

You may also enjoy Pockets of Peace in Ukraine, Spring 2022: Care through Music, A Blank Newspaper, How to Make a Fruit Basket for the Aliens, Lament for Syria, and items with the tag ‘artivism‘.

Oliver Richmond is one of several scholars who have studied ‘ArtPeace’, as he terms it; you can get a flavour of his arguments in this article: Richmond, O. (2022) ‘Artpeace: validating power, mobilising resistance and imagining emancipation‘, in Journal of Resistance Studies Vol. 8 Issue 2, p74-110.

If you want to see some terrible but entertaining depictions of peacemaking with aliens, watch Mars Attacks! (1996) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978). If you want to see some uplifting stories about alien invasion and humanity’s common goodness and peacefulness, read Contact by Carl Sagan and watch The World’s End (2013).

Arden Henley, April 2023