Take heed, dear Friends, to the promptings of love and truth in your hearts. Trust them as the leadings of God whose Light shows us our darkness and brings us to new life

Religious Society of Friends in Britain, 2013, Quaker Faith and Practice 1.02

A good end cannot sanctify evil means; nor must we ever do evil, that good may come of it.

William Penn, 1693, Quaker Faith & Practice 24.03

Peace and spirituality are intertwined in the history of religion, but what would religion look like if non-violence was the central pillar by which to live? Buddhism provides one answer to this question; however, this museum entry focuses on Quakerism, a branch of Christianity that emerged during the 17th Century, amid the Civil War in England, and believes that God exists in every person. This is the first part of a five-piece series of entries focused on Quaker Faith & Practice, the book written by the British Society of Friends (Quakers), that acts as a guide for Quaker values, behaviours, and worship. I focus on Chapter 24 in particular, which details Quaker testimonies towards peace and non-violence. I attended a Quaker school myself, and so this series of articles has involved critically re-examining the ways in which I was socialised towards visualising peace, in particular how attitudes towards peace are thought to be the central guide to people’s actions.

Introducing Chapter 24

Chapter 24, Our Peace Testimony, features the thoughts and declarations of many Quakers on peace. The chapter, as well as the book as a whole, is designed to guide Quakers in their thoughts and actions, but not as a prescriptive set of instructions to follow. The introduction describes the book as a discipline: that is, discipline as advice and guidance rather than as the enforcement of certain rules. The testimonies of Chapter 24 therefore all approach the concept of peace in slightly different ways, showing the development of thought and attitudes over time and the conflicts through history that have challenged Quaker principles of non-violence again and again.

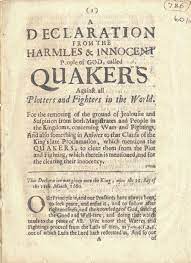

The beginning of Quakerism can be traced back to George Fox, amid the increasing political chaos and religious diversity that accompanied the English Civil War in the mid-17th Century. The printing press had allowed for the proliferation of cheap religious pamphlets, which challenged the Church of England’s position as the only legitimate religious authority[I]. This brought many preachers and religious groups into tension with the King, leading to various forms of suppression and persecution. Following the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the King outlawed various religious movements, including Quaker meetings, and demanded that all members take an oath of allegiance. It was in this context that Fox, along with several other prominent early Quakers, presented a Declaration to Charles II.

The declaration’s full title speaks of “plotters and fighters” as it was written to distance the Quakers from Fifth Monarchists. Its publication marked a shift from individual pacifism to a more explicit, corporate witness among Friends. It can be seen as a political and strategic document, intended to convince others that Quakers, despite their revolutionary religious beliefs, posed no threat because they rejected the use of violence. The statement seems to have been easily accepted by other Quakers and has remained an enduring and distinguishing characteristic of Friends for over 350 years.

https://www.quaker.org.uk/documents/the-quaker-peace-testimony-pdf

The declaration was a refutation of the rumours that Quakers were involved in a plot to usurp the new King along with other Christian religious factions of the time. It denounced fighting with any ‘outward weapons’. There is certainly an attempt here to project Quakerism as harmless and innocent; they are after all trying to avoid being tried for treason! There is a certain pragmatism to the declaration, and to the thoughts and actions of early Quakers in general.

Despite this, the declaration is still deeply subversive, in that it challenges some of the core societal tenets of the 17th Century: militarism, monarchical rule, and the idea that there is a higher power than the King which prohibits harm to others. It is ironic that this declaration, made to protect those who made it from persecution, ended up becoming so central to the values of many within the Quaker movement, and eventually led to people being persecuted for those same values (for more on this, please see my second entry in this series on Quakers and Conscientious Objection).

The subversive nature of the Declaration is echoed by another early Quaker, William Penn. Given a portion of land by the King on the west bank of the Delaware River in the United States, which was named Pennsylvania after his father, Penn conducted a ‘Holy Experiment’ in 1681: a new way of governing based on the fair treatment of the Indigenous Leni Lenape, a lack of any soldiers, and a democratic style of leadership that included freedom of religion, universal education and an expanded franchise (women were still not allowed to vote, however). This new society obviously presented a challenge to the dominant ways of thinking in the 17th Century, enshrining Quaker ideas of peace and equality at its core. Penn’s experiment shows that Quaker values on peace must be contextualised within a larger approach to life, of finding value in (and equality between) each and every person. Ideas such as democracy and universal education fit into the same belief system as non-violence; they are all needed for the fuller Quaker visualisation of peace.

Much of what Penn envisioned in Pennsylvania outlasted him, but some of the more idealistic elements did not, and that points us towards a challenge at the heart of the Quaker visualisation of peace: are these values compatible with the pragmatics of living in human society? Additionally, is any personal value worth holding onto in the face of violence and the threat of persecution or death? This debate survives as a central division in the religion in the 20th Century and beyond.[ii] These questions are explored further in the other pieces in this series, but it is important here to recognise that they were baked into the Quaker understanding of peace from the start, which emerges as complex and capacious, not simple or reductive. There was never a general societal expectation about peace and non-violence; in fact the Declaration to Charles II describes war as an inevitable part of human nature. Instead, non-violence is meant to guide the individual behaviours of Quakers. As noted above, Chapter 24 of Quaker Faith & Practice is written as the testimonies of individuals, discussing how they used non-violence in their own lives. It is meant as advice, not as dogma.

What do you think?

- How differently do different religions visualise and promote peace?

- How do different religions model the complex relationship between inner/individual peace and peace in the world?

- Do some of your own ideas of peace originate in religious beliefs or practices?

- How does your visualisation of peace affect your everyday life? Does it guide your actions in any way?

- Do you think values and ideals, religious or otherwise, can really make a difference in the face of violence, or even death?

- Should you ever do a bad deed if the outcome is good; even if that deed does violence to others?

If you enjoyed this entry in the museum…

You might also enjoy other articles in this series on Quaker Faith & Practice: Quakers and Conscientious Objection, Relief from Suffering, Mediation and Disarmament, and Religion, Idealism and Pragmatism.

Joe Walker, December 2022